Episode 7: Gemma Lloyd & Lara Goodband on wild card witches, curating museum spaces in a changing climate, & the power of tears as big as plums

For Episode 7 of The Heart Gallery Podcast, Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer talks to curators Lara Goodband and Gemma Lloyd.

Lara and Gemma are curators of Earth Spells: Witches of the Anthropocene, happening now at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter. The exhibit features works from some incredible artists from around the globe: Caroline Achaintre, Emma Hart, Kris Lemsalu, Mercedes Mühleisen, Grace Ndiritu, Florence Peake, Kiki Smith, and Lucy Stein. Lara Goodband is the Contemporary Art Curator and Programmer at Royal Albert Memorial Museum, and Gemma Lloyd is an independent curator. Listen to Lara Goodband and Gemma Lloyd to be spellbound by the intrigue and relevance of witches throughout history and for our world today...

See glimpse of Earth Spells: Witches of the Anthropocene below. The podcast transcript is also available below.

Mentioned by Lara: Britain's Royal Albert Memorial Museum returns artefacts to Siksika First Nation.

HW from Gemma: "This is a bit of a strange one. We got my 8-year-old son a moth trap for his birthday last year. I feel that it opens up a huge world, this nocturnal world that we never get to see, [even in the city] (I'm saying this from London). We put this moth trap out at night, and from early spring right through to autumn it's absolutely remarkable what is under your nose in your own environment, what you can see if you have the means to capture it. It is extraordinary and will give you a bigger appreciation of your position in the environment and in the world. If you can find out about another species that's within your own environment, I kind of feel like that gives you an understanding of your place within it."

HW from Lara: "I would like to suggest that everybody reads Amitav Ghosh's book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable."

Connect with us @Lara Goodband, Gemma Lloyd and @rebekaryvola.

Thank you Samuel Cunningham for podcast editing.

Thank you Cosmo Sheldrake for use of his song Pelicans We.

Podcast art by Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer.

Select Earth Spells ~ commentary from the podcast on exhibit pieces:

#1: Emma Hart, Good Vibrations. 2023.

Lara: “Emma Hart is an artist who works with ceramics and she makes sculpture. Witches isn't a theme that has come up for her before, so we were quite interested in what she would do. She came up with this new commission, Good Vibrations, which includes 13 ceramic disc-shaped pieces that have a kind of target pattern painted onto them, and she's grouped them together like a coven of witches. She's interested in - and this is a theme that runs through her work - the power of speech: what speech can do, and how witch spells are a form of that. Speech can affect change, and there are people out there like Greta Thunberg who have the power with their words to cause a ripple effect across society.”

(Photo credit: Emma Hart/Ollie Hammick).

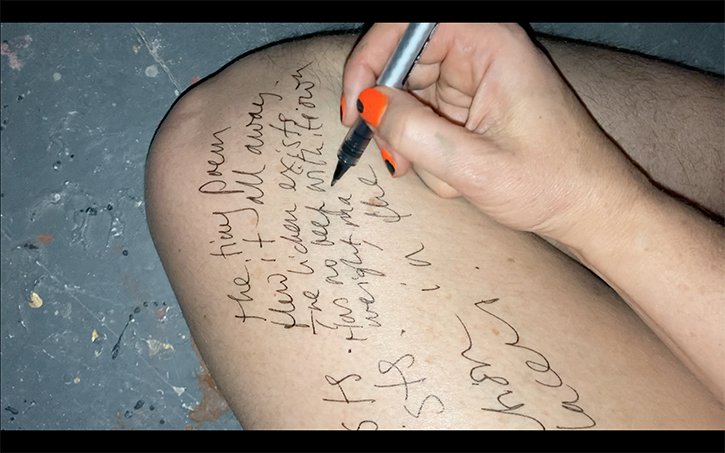

#2: Florence Peake, The Lichen Exists. 2023.

Lara: “So we're really fortunate that we've been able to work with Florence Peake for one of the new commissions. And she not only did she come and visit the museum and hold the cauldron that belongs to Elizabeth Webb and dates from around 1900, and felt its aura, but she spent quite a long time with it in the store. It's never been shown at the museum in public before. So this is a star billing, and it's central to the exhibition and the ideas; although it is quite a small little crock, it's a very powerful piece. She then went to visit Dartmoor, which is very close to Exeter and is a traditional site of many myths and ancient burial sites. It’s been explored by many writers and artists over the last couple of hundred years.

Florence had a healing ceremony on Dartmoor with a shaman. It was very powerful for her, and the new body of work came out of that experience in that place and her relationship with the land and the earth there. She made ceramic pieces that have come out of the memory of the feel of the moss that she lay down on at the bottom of the moor. She's written poems and text which appear on the wall, but also as painted text on the hangings, and people can walk amongst these hangings. She originally trained as a dancer, she’s a somatic movement expert, and she wanted people to be able to be part of that choreography. And so it's a very beautiful installation and also emotional. I think this symbolic, chaotic relationship with the earth really kind of drove some of the ideas for the curation of the show.”

(Below: photo stills from Florence’s film via the artist; Photo of Florence with the Elizabeth Webb cauldron via RAMM).

#3: Grace Ndiritu, Labour Birth of a New Museum. 2023.

Gemma: “One of the works in the show is by Grace Ndiritu, who is a British Kenyan artist. Grace invited a group of expectant mothers to come to the museum, and she held a kind of shamanic performance for them to understand and identify the spirit name for their children. Lara was telling me the other day that she had lots of young people in the gallery space, and they sat there to watch this film that is a recording of Grace's ceremony. They were hugely engaged with it, it envelops you in the space. It was really incredible to hear how engaged, how quiet, how focused they were, and to imagine what they might be taking on board.”

Lara: “Grace has created a carpet for her installation as well […] So when you step over into that space, you take your shoes off. Even today with the MA Fine Arts students… Once they stepped over and they'd gone through the act of removing their shoes, entering this space and really engaging with the work [was] really quite transformative.”

Gemma: “That's quite interesting as well, isn't it? Because I remember reading a while ago that in certain Scandinavian education settings, especially in the younger years, the children are encouraged to take their shoes off. And they've demonstrated that they absorb more by doing that because you instantly put on some slippers and maybe just slightly feel at home somehow, and you engage with things differently.”

Lara: “It's a threshold, isn't it? I think Grace has set up a situation where you take your shoes off and you understand, “I'm going to contemplate what's happening here and really think about it”.”

(Below: photo stills from Grace’s installation).

#4: Mercedes Mülheisen, Lament of the Fruitless HEN. 2015.

Lara: “There's a video installation with objects by Mercedes Mülheisen called "Lament of the Fruitless HEN."And what Mercedes has to say about what a witch is, I just love. She talks about a witch being someone who can cry tears as big as plums. And I just thought that was so poetical. Having spent some time with Mercedes now, I would say she's a witch. She lives in the forest in Norway.”

Rebeka: “It's like a deep, dangerous capacity to care that's really powerful. Yeah, and it's an amazing piece.”

Lara: “It seems to have struck a chord both with the critics and also with our visitors, the audience to the museum.”

Gemma: “I think I saw Mercedes' work at the Astrid Fernley Museum in Oslo. And she is a really remarkable artist who creates these kind of very unsettling, melancholy scenes with video. And like Lara said, the scripts, the protagonists of her videos, use words that are absolutely phenomenal, aren't they, Lara?”

Lara: “Yeah, and actually Mercedes' work, "Lament of the Fruitless HEN," and the visuals to that, I think were quite a key sort of mood for us in terms of curating the show. We saw that work early on online and we kind of felt as though, yeah, this is it. It's got this "Twin Peaks" feel about it, this sort of disturbing…”

(Below: photo still from Mercedes’ film).

Podcast transcript:

Note: Transcripts are generated in collaboration with Youtube video captioning and ChatGP3 and are not extensively edited.

[Music]

Hello and welcome to Episode 7 of the Heart gallery podcast, with me, Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer. I am an artist, creative advisor, and visual communicator, and I’ve worked primarily with climate and humanitarian organizations for the last decade. I also have a personal art practice where I explore relationships between individuals, other living beings, and our planet. I created this podcast to inquire into the various roles that art can play in helping us create deeper connections with our surroundings and others.

Today i’ll be talking to two guests about … witches. What do you think about witches? When I heard about an art exhibit in the UK titled Earth Spells: Witches of the Anthropocene, my attention was captured. For some definitions: the Anthropocene is a proposed geological epoch within which humans have had a substantial impact on our planet, and witches…. Well, witches are complex. They might have featured prominently in the stories of our childhoods. They were present in some of my favorite eastern european folktales that I grew up with. As I got older I got more interested in witch history, which is marked by darkness, sadness, and a lot of horror for those that had the label - by choice or not - of witch.

The Salem Witch Museum estimates that the peak of the European witch trials, roughly between 1560 and 1630, saw fatalities of around 50,000 individuals who were burned at the stake. These individuals, primarily women, were often deeply connected to their environments, were medicinal leaders, and had alternative views of society. Witches and their persecution are of course not limited to European history. There are examples of past and present witchcraft practices across the Afro-Latin diaspora, asia, the Middle East, and the African continent.

It feels like witches are more front of mind in societal discourse recently, in narratives about alternative models for relating to the world, healing society, and inviting new perspectives. Because of that, I was so thrilled to have the opportunity to meet with the curators of Earth Spells: Witches of the Anthropocene, happening now at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter. The exhibit features works from some incredible artists from around the globe: Caroline Achaintre, Emma Hart, Kris Lemsalu, Mercedes Mühleisen, Grace Ndiritu, Florence Peake, Kiki Smith, and Lucy Stein. It’s curators are Lara Goodband, Contemporary Art Curator and Programmer at Royal Albert Memorial Museum, and Gemma Lloyd an independent curator. I hope you enjoy.

[Music]

Rebeka: Gemma Lara, it's so lovely to be here with you.

Lara: Thanks for having us.

Rebeka: I'm so thrilled to be chatting with you today. I mentioned to you this is my first podcast with two guests, so this will be interesting. I tend to get quite deep and personal with people, and I think today we'll be more topically focused, but I'm still looking forward to letting the audience get to know both of you and also get to know your incredible work, specifically one particular project that is going on right now.

To start, I wanted to ask you to do a little bit of a storytime, and I'd love to hear about the roots of your interest in both art and the environment, art and your surroundings, your natural surroundings, because those are themes that we're going to be getting into. And I wonder if you wouldn't mind both of you sharing either one story that connects the two or sharing how you got into both of those different spaces, how your love, your passion, or however you would characterize it, how that developed in your life.

Gemma: Okay, so I grew up in a town in Ipswich, Suffolk, in East Anglia, and I think it was quite clear from an early age I was interested in art but from the perspective of making work. I went to Art School in Nottingham, and then I decided I really had to move to London. I wanted to be in London, and so I started working in a project space in London, and I was doing all different kinds of jobs and just kind of getting out there, I suppose. And then after a few years, I ended up at the RSA, an arts and ecology program, and that was the program that was initiated to be a catalyst for artists thinking about climate change. We did a number of projects there that were around, you know, we had debates, we had discussions, we had commissions, and lots of overseas trips as well for artists to immerse themselves in different cultures and different environments and work out on the ground what was happening. And so that was kind of like a really formative experience and role. I was there, I think, for about four years until I went back to study and did an M.A in curating at the Royal College.

Rebeka: Gemma, did you even enter that program? And was there already some sort of nascent attachment to the environment in nature?

Gemma: It wasn't, it really wasn't as kind of organized as that. I mean, I'd been working in some galleries and one of the people that I was working with - she was about to leave the RSA for another job - and she said, "Hey, you'd be perfect for this. We're looking for someone to kind of coordinate a whole program of activity." And so, I must have been about, I guess I was about 21, 22 or something at the time, and I kind of was just... I didn't know which direction to take at that point, you know? I was in London and I found it such an exciting city, and I just wanted to explore everything. And she said, "Why don't you - why don't I introduce you to the director?" And then, anyway, I did, I met her, and her name's Michaela Crimmon, really inspirational curator. And she then said, "Yeah, why don't you apply?" So I did, and yeah, I got the position there. But it, I have to say, it wasn't driven by that as a subject, it was more fluid, I suppose.

Rebeka: And your love for your natural surroundings has grown since then?

Gemma: Yeah, hugely. And I mean, that was obviously, you know, four years of really solid, focused work, but then it's been... it's been a topic that I've returned to in other projects. And I mean, maybe we can talk about this, but it was also where Lara and my own path crossed later on, a previous project that we curated for Hull, UK City of Culture, which was called "Offshore: Artists Explore the Sea". And that was a series of commissions and existing work that we curated for two spaces, the Ferens Art Gallery and the Hull Maritime Museum. And so, that was how we met, and that's the reason we came together to work on Earth Spells: Witches of the Anthropocene at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter.

Rebeka: Fantastic, thanks for bringing it all around. And Lara, I wonder if you wouldn't mind taking us back to the roots of your interests in art and environment?

Lara: Yeah, sure. So, I've been thinking a little bit further back to my childhood, and I grew up in Liverpool, but I was really fortunate to have two great-grandparents who took us on fantastic holidays to Wales and Scotland. And my gran was a great lover of birds and could identify birds and wildflowers. And I don't know whether you had them in the States, and whether Gemma probably remembers the I Spy books... They've come back again recently, and I absolutely loved these with my cousins, you know, making sure that we identified as many birds and flowers and other... It was normally the natural world. There are I Spy books kind of linked to... because we bought them for our holidays.

And I also really enjoyed having a secret name and, you know, keeping that name secret from all the adults. And I just really felt a connection. And subsequently, the whole relationship with the sea and the coast, and obviously, we live on an island, has informed some of my other exhibitions. I did a big Cultural Olympiad project called Sea Swim and worked with a number of artists around the littoral space, you know, between the land and the sea. So, I feel like those holidays in other parts of the British Isles had an impact.

Going to visit my auntie in Ireland and exploring the west coast of Ireland as well as really, um, helped to inform my kind of care and love of the natural world. And then, um, when I was thinking about what I might do before I went to University between my first and second year doing A-levels, I was, um, really strangely kind of immediately promoted to Arts Editor of a local newspaper in Liverpool called The Crosby Herald.

Rebeka: Congratulations!

Lara: I know I was only 17! and, um, I, it was when uh, Tate Liverpool was opening, uh, where I was really lucky, you know, to be living in Liverpool at the time and to be writing for this paper. And I was invited to go and review the new Degas show that was opening. It was really bizarre when I think about it, fearless because I was 17, to know anything different, yeah, yeah. Um, and I was just there, you know, asking questions, one of us, um, and then, um, while I was there, I found this room that was just full of newspapers and I just thought, "This is crazy!" And recycling was quite new, so um, I borrowed my grandpa's car and filled it up with newspapers and just started recycling and getting everybody else into recycling, and my friends and family. And yeah, I just remember that being a kind of big start, clearing out the newspaper.

Rebeka: What a beautiful origin story! Do you remember any favorite birds or flowers that you identified?

Lara: Yeah, well, it's kind of come back to me here now because we've got quite a few bird feeders, and although I was sad to say goodbye to my cat in Autumn 2019, it's been a great boon for my own garden and the bird life. And I've been watching blue tits coming to check out our nesting box. And we're really fortunate that we had them nest in our front garden there in our box, but this year we're hoping we're gonna get two broods, one in the front, one in the back.

And we've had a robin and we've got a lot of sparrows. We've got, um, it's been really quite cold here the last few days, particularly for Devon.

Um, and it's just, it's just so, it's a joy to sit and watch. But I do remember trying to identify the different types of tits with my gran, and you know, greater blue tern, and she always carried binoculars and took us to places like Martin Mere, which were really inspirational even during my A-level for the subjects that I studied then.

Rebeka: How beautiful. We have a lot of robins here too, and you're reminding me that I just moved to a place that has a garden, and you're reminding me that I need to figure out how to be interacting and feeding and supporting these species, especially as spring is springing. Thank you for sharing that. And I want to immediately come to the exhibit that the two of you are working on together - have been working on together - that is going on right now at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum. Earth spells: Witches of the Anthropocene, which is so incredible, and I've read so much about it that I feel like I've seen it. You've had some incredible press coverage, so congratulations on that. And I wonder if you could just explain from your perspective: what this exhibit is and what you're trying to do with it?

Lara: Yeah, so maybe it's also interesting to think about what this exhibit isn't as well because actually, Lara approached me. So, I'm a freelance curator. Lara is the Contemporary Art curator based at the Museum, and Lara said to me, "Hey Gemma, would you be interested in working together? I've got the beginning of an idea for a show. We've acquired a cauldron from the White Witch of Devon… Yeah, yeah. So, how's about we... We cook up a show that relates to that and relates to witches and the way that over time, particularly women have had this relationship with the natural environment, which has been perceived as, you know, suspicious, um, suspect, and let's think about this.

So, we started to think about what we'd seen, and there are already a few precedents for exhibitions that had taken witchcraft as a central theme, but what we were really keen on was we didn't want to necessarily bring in the usual suspects. So, there are some artists that have a kind of synonymous now with witchcraft, and you also have artists who are practicing witches or would say they're witches first and foremost, that they make work around that. We were kind of a little bit more keen on bringing in some wild cards, and we used it in the press release, but we've got this term "witchiness," which is very imprecise at all, but we were kind of intuitively looking for artists whose work was somehow unsettling or disturbing, or there was something about it you couldn't quite explain, and those artists maybe hadn't already thought about witchcraft in their work.

For example, Emma Hart is an artist that works with ceramics and she makes sculpture. She isn't a theme that has come up for her before, so we were quite interested in what she would do around this theme. So, she came up with this new commission which was "Good Vibrations," which includes 13 ceramic disc-shaped pieces that have a kind of target pattern painted onto them, and she's grouped them together like a coven of witches. She's interested in how, and this is a theme that runs through her work, which is the power of speech and what speech can do, and the Witch's spell is a form of that, and that it can affect and change, and that there are people out there like Greta Thunberg, who Gemma has mentioned, who have the power with their words to cause a ripple effect across society and make change.

Gemma: So yeah, I guess we were quite interested in bringing together new voices from a really broad range of perspectives and also mediums as well. So, we were saying actually, you know, this exhibition, this could have been huge. It could have been, you know, we could have included four times the amount of artists that were in the show, but we were so keen, you know, to present a range of voices but also from very different mediums.

So we have Jacquard tapestry, we have ceramics, we have video and objects, and painting. So a really broad range. And it's interesting, actually. Lara was telling me the other day, and it'd be nice to share that, but you had a group of students come in, didn't you, Lara? And that's sort of the materiality of the exhibition seems to be something that the visitors are really responding to.

Lara: Yeah, yeah. So when we, I mean, I think we were working together where we're interested in, um, such a diverse range of artists' practices. And we're always really thinking about the visitor, the viewer, how people engage. And I know myself that I, I first and foremost engage in a kind of visceral bodily way. And I think that, you know, where we're a museum, we don't always show contemporary art. So for some people, we're introducing these artists for the first time and these kinds of artistic practices. So we want them to feel really comfortable and that they can almost interact and engage with.

So we're really fortunate that we've been able to work with Florence Peake for one of the new commissions. And she not only did she come and visit the museum and hold the cauldron that belongs to Elizabeth Webb and dates from around 1900, and felt its aura, but she spent quite a long time with it in the store. And it's never been shown at the museum in public before. So this is a star billing, you know, and it's central to the exhibition and the ideas; although it is quite a small little crock, it's a very powerful piece. She then went to visit Dartmoor, which is very close to Exeter and is a traditional site of many myths and ancient burial sites. It’s been explored by many writers and artists over the last couple of hundred years. Florence had a healing ceremony on Dartmoor with a shaman.

It was very powerful for her, and the new body of work came out of that experience in that place and her relationship with the land and the Earth there. She made ceramic pieces that have come out of the memory of the feel of the moss that she lay down on at the bottom of the moor. She's written poems and text which appear as a very visible poem on the wall, but also as painted text on the hangings, and people can walk amongst these hangings. She originally trained as a dancer, a somatic movement expert, and she wanted people to be able to be part of that choreography. And so it's a very beautiful installation and also emotional. And I think there's a lot about this thinking around having a symbolic, chaotic relationship with the Earth that really kind of drove some of the ideas for the curation of the show.

Rebeka: "I'm so curious. I'm just looking at my bulletin board over here. I just, um, on another podcast, I heard this incredible poet named Jane Hirschfield. She was speaking about art and poetry, specifically about how art is a vessel for transformation. And curators, I mean, it's such a powerful role. The fact that you're almost like God-like, or maybe I should say, you're almost like witches yourselves, where you're trying to craft this experience that will bring about a change. And Lara, you mentioned that you were focused on this visceral experience yourself. And I'm wondering how much you're trying to deliver a specific experience to your visitors. Lara: Yeah, that's interesting, isn't it, Gemma? When we thought about where we were placing the works and I was talking to some students about that today, but yeah, you go ahead.

Gemma: No, I was just gonna say, actually, another really interesting consideration for us was, as Lara said, this is a museum that has an incredible collection of material. It's not a contemporary art-focused museum or space. And what I was really interested in as well was that it was a really interesting proposition that children and young people make up a huge part of the audience there.

So, another of our considerations was, well, how do you make a show that can also appeal to younger audiences as well? And we've got the title 'Anthropocene' there, which could be perceived as a challenging word in the title. But within a museum that has flint displays that deal with all kinds of eras and epochs and long words, then it kind of felt fitting, you know? And to bring that as a sort of, you know, if you don't know about the Anthropocene, maybe you will learn a bit more about what that means as a geological time period.

And one of the works in the show is by Grace Ndritu, who is a British Kenyan artist who invited a group of expectant mothers to come to the museum, and she held a kind of shamanic performance for them to understand and identify the spirit name for their children. And Lara was telling me the other day, you know, she had lots of young people in the gallery space, and they sat there to watch this film that was recorded of Grace's ceremony. And they're hugely engaged with it, and the surrounding kind of envelops you in the space.

And that was really incredible to hear, you know, how engaged, how quiet, how focused they were, and what they're taking on board as well.

Lara: So Grace has created a carpet for her installation as well, so that very much defines almost like the magic ring that Peter Brooke talks about. And so when you step over into that space, you take your shoes off, obviously. And she's chosen a very specific image of her mother and child from a photograph of the commune that it depicts. So, you know, she's thinking about motherhood.

And even today with the MA Fine Arts students, you know, once they stepped over and they'd, you know, that the act of removing your shoes and entering this space and really engaging with the work is really quite transformative.

Gemma: That's quite interesting as well, isn't it? Because I remember reading a while ago that in certain Scandinavian education settings, especially in the younger years, the children are encouraged to take their shoes off. And they've demonstrated that learning, they absorb more by doing that because you instantly put on some slippers or something or just slightly feel, you know, at home somehow, or you engage with things differently.

Lara: It's a threshold, isn't it? I think Grace has set up there where you, you know, you take your shoes off and you understand, right? I'm this, I'm going to contemplate what's happening here and really think about it.

Rebeka: Yeah, it's a really unusual Museum experience and I love that. And the little I know about Grace and her work, and I think also what she was trying to do with your exhibit, so she's trying to challenge and change the shape of what museums are and what the museum experience is to people. Was that a part of your desire to have her be a part of the show?

Lara: Yeah, definitely. And she's been working on a whole series of work called the New Museum. She's very interested in thinking about how we engage with the history of the collections in the museum and what that means at a point when we're thinking about repatriation, that's, you know, returning object to the cultures that it came from and how we work with the communities whose objects may have been removed at force. So yeah, it's been a really interesting process, excellent choice.

Rebeka: And I'm curious, this is just going a little bit bigger picture for a second. I want to go back to the Witches of the Anthropocene, but to go a bit bigger picture, how, as you as curators and given the longer careers that you have, how has your sense of the museum space changed and shifted? Like you're working on the subject matter now, engaging with artists that are challenging museum spaces. Do you feel like you've been having that discourse with yourselves as well?

Lara: Um, yeah, we, RAMM and Exeter, we are constantly kind of interrogating those themes because we have a designated World Cultures Collection, and we recently returned a whole series, you know, a whole group of objects to the Blackfoot and the Siksika Nation in what's now Canada last year. They're really beautiful objects that belong to them, and they came and did a smudging ceremony at the Museum, and in exchange, gave us new objects from their community, which was, it was so wonderful, such a beautiful and powerful ceremony. And, you know, that's been going on for a while, and it will continue, you know, as different communities from across the world ask for their works.

Rebeka: Incredible. Gemma, I wonder if you want to share anything from your experience?

Gemma: I guess I've come from a slightly, yeah, I'm in a different position because I'm not affiliated with the particular museum or gallery. I mean, well, I was. I was. Your question actually made me think slightly about more specifically the engagement artists have had with the climate. I mean, I mentioned earlier that I was working on the Arts and Ecology program back in the early 2000s, and I mean, certainly at that point, we hope to be this catalyst to encourage artists.

And I remember when we were researching, you know, who could we reach out to, who can we bring in, who can we engage, who are the artists that are working with the environment. I mean, there were lots out there, but that's also been an enormous sort of explosion of people that are willing to engage with this topic. I mean, even then, it felt at the time we were slightly, you know, kind of approaching people and "oh, quite what I'm really dealing with" or "I'm not quite interested in it at the moment."

And so yeah, it was really interesting now because in everything we do, you know, I also do like I work on public art commissions, and so many of them recently have been driven by human-made changes to the environment. But also just thinking in terms of sustainability in the way that you practice as curators, and you know, right down to like the materials that artists are working with and is that ethical? Where do you want to work? Who do you want to work with? I mean, the whole landscape has changed. I think on that front too, and you see

Rebeka: Do you have a sense of, I guess, like future casting a little bit: I'm curious, as curators, do you feel like you need to be looking to the future to try to predict, evaluate where museums, where curators are going to have to be going in the coming years and decades?

Lara: That's really an interesting question. Yeah, sometimes I feel quite terrified by the situation that, you know, Western Capitalist Society is I mean that we're in and how desperate I am for people to make changes of behavior to ensure that we limit the extreme damages to probably not as much us but, you know, already people in the southern hemisphere are suffering so much.

And yeah, I feel like already our museum has suffered from like heavy rainfall and a roof leak because it was a really dry spell and then it was really, really heavy rain, and that actually meant that our exhibition couldn't be shown in the galleries it was originally planned for and at the original time. So, you know, that is likely to be down to climate change, and yet even I, who have really engaged both emotionally, mentally, and try my actions, and, yeah, I'm just coping with it, you know, we're just taking steps to mitigate the effects of our Museum was created in the middle of the 19th century, and it is really difficult to think about how it may look in the future. We won Museum of the Year 10 years ago, and that's a big prize for the UK, an art fund prize. So, the museum was thrilled with that, so we have lovely new spaces, and we're really lucky that our exhibition is in those beautiful spaces, but trying to imagine the next 10 years when I already know that the building isn't able to cope with some of the climate changes.

Rebeka: Yeah, thank you for sharing that. Gemma. I wonder if you have anything to add on that as well, like what you think and also about speaking about the role of museums. It seems like from my perspective, I have not studied Museum spaces. I'm new to the art world. I come more from a policy background, but my sense, like what I've noticed, is that museums are shifting. I feel like there is this growing sense of responsibility, Laura, like the returning of objects, re-examining how these collections came to be, but also just how they're participating in societal discourse. And I'm curious how that is also going to be potentially growing or shifting.

Gemma: Yeah, I mean, I think it's so. I see the role of a curator as well as a kind of, I suppose, a facilitator. And I personally don't feel like I'm a curator where I need to be right at the forefront or super visible or have this huge ego related to it, because I think personally, my role is that okay, it's the artists and the artwork. And I think what's really interesting is what artists are bringing to all of this debate. Grace, for example, when we spoke to her about participating in the show, she was really interested in something that she had been dealing with for such a long time, but people just, for one reason or another, just didn't quite take it on or weren't interested in it, and she couldn't find a home for it. But now all of a sudden, people do seem receptive to that.

Lara: I think as a curator, you really have to listen in. And it's interesting what you say about future casting and listening because there are artists out there who are thinking in really intelligent and novel and innovative ways. And it's about as curators to take a step back and hear them out and see, okay, well, actually, here is the platform. Let's see what you can bring to that and what do you want to do with it? So, I see my role as someone that can bring in artists' voices and responses. I think policy makes a really big impact on what the opportunities are for artists, museums, and gallery spaces.

We've been very fortunate to get Arts Council England funding and to continue as what's called a national portfolio organization. But sometimes policy can be instrumentalist as well, so it means that the expectations around what the artist should be making because the funders are directing their funding in a particular area of artistic practice. And when I'm thinking about areas, not just artistic practice but geographic areas as well, we have priority areas for Arts Council England, and then we're funded by local authorities, which is fantastic. But local authorities are very underfunded currently in England.

Rebeka: Fascinating, so you know that does have an impact, and I want to, we only have a few minutes left, and I want to be very respectful of your time, but I really want to go back to witches. And when I first heard about this exhibit, I was just so enchanted. I was like, "Oh, witches, isn't that so lovely?" And I have this idea that I'm a descendant of, you know, some sort of Eastern European witch colony, which I haven't told anyone before. But, but like, that was my initial thought. And then I delved deeper, and I was talking to my partner, my husband about witches. And, and I want to hear you speak more about your interests in witches and whether it actually came from this Elizabeth Webb cauldron or whether there was some interest before. And if we could just like speak more about the relevance of witches today, yeah.

Lara: So for me, um, it kind of coincided. The two, the two things just before I started the job at the Museum in Exeter, I met three witches in an event for the Women of the World Conference that was had taken place next to, and they were talking about their relationship to the natural world and ecology. And it was only a few weeks after that that I met the cauldron in the stores, uh, had the museum. And so those two things collided.

And I, you know, we'll, we both started, we're reading about witches and Sylvia Federici's um, book and about the history and persecution of women and Witchcraft. And, you know, there was an exhibition on doing a tour as well. And so there were some kind of historic thinking around Witchcraft and its influence on events. And I just think that reclaiming the term so that it's no longer this um, term of abuse and unpleasant, um, or even scary kind of Disney pointy hat which was really important.

Gemma: Yeah, I mean, yeah, I grew up in, um, I mentioned in East Anglia where we had Matthew Hopkins, witchfinder general. So I remember thinking, you know, like at school, there was this mention of this figure, you know, who would hunt down witches, this male. And it's, I mean, that's sort of always I've carried that. And I remember even the um, some of the people I went to school with at high school with their parents were extras in the film version of it. And so that was quite interesting, yeah, funny. But yeah, I think it also, the thing that we should say about Exeter as well, which I think is really important, is the last um, witches to be tried, um, and then hung in England, um, you know, in the late 17th century was in Exeter. And the site of the trial is at the castle ruins just behind the museum.

So some of the artists that we've worked with have been to that site. And Lucy Stein, who's one of the artists who's based um, down in Cornwall, St. Ives, and she was really fascinated by that site. She does um, self-identify as a what she calls an artist witch or half-witch. And, and she's produced a whole body of paintings in response to the experience of going to that site and seeing the cauldron and working with other collections.

Rebeka: What do you think was lost like what do you think Society lost during that whole awful period of persecution?

Lara: I think it lost a huge amount of knowledge. You know, women traditionally held this knowledge that was then you know kind of taken away from them and brought back into the realm of the professionalization of medicine that was then moved into like the sphere of men.

Gemma: and, and it's yeah. I mean, I think it's that knowledge and that connection and that understanding. And I mean, when you're thinking about all of these uh, rewilding efforts that are going on across the world, where you know, for example, beavers are reintroduced, you know, and that that's had a huge impact on preventing flooding because you know, we live in harmony with non-human species. And we're sort of rediscovering that again now, that actually, you know, we're part of an ecosystem. We're not outside of it, which feels like, you know, we've gradually sort of come to believe that we're superior to it all. And I think those, you know, the witches of the past, many of those would have been women who just intuitively understood, you know, how to live in harmony and symbiosis with the natural environment, how to get the most out of it, and work with it for the benefit of everyone.

Lara: Yeah, it was also a really unpleasant way in, in a city like Exeter, for example, that there's been a lot written about and the history of witches in this particular city and where those women who were located, you know, in a particular part of the city outside of the city walls would very quickly become defined as witches. But it was really to do with um, poverty, and also it encouraged, uh, you know, a kind of spying, an unpleasant way of dealing with other people. So you could easily be accused if you just looked in a certain way or dressed in a certain way or didn't obey the patriarchy basically. And so it was a way of like kind of, you know, conforming a society and giving men power.

Rebeka: I hope that the fact that these conversations that Gemma you were mentioning to me before we started recording that like there's this trendiness to which is right now, and I hope that that's not only positive for the region you're speaking about now, but also for indigenous populations also, you know, where we have really dark Colonial histories where I think a lot of community practitioners were also targeted in different ways. And I wonder just, just to close out if if you could share like who who do you think are witches today in our society? Of course, it's a very broad question, and then I would ask one more question if I can, well.

Lara: I guess I don't know. I'm gonna just turn that around a bit because... I'm gonna pick something. Emma Heart actually made a proposition that maybe Greta Thunberg is a witch, you know? And I thought that was quite an interesting concept as well. That the things that she has to say, she's casting spells and trying to force through change through speech. I think in the show, there's a video installation with objects by Mercedes Mulheisen called "Lament of the Fruitless Hen." And what Mercedes has to say about what a witch is, I just love. She talks about a witch being someone who can cry tears as big as plums. And I just thought that was so poetical. Having spent some time with Mercedes now, I would say she's a witch. She lives in the forest in Norway

Rebeka: It's like a deep, dangerous capacity to care that's really powerful. Yeah, and it's an amazing piece.

Lara: It seems to have struck a chord both with the critics and also with our visitors, the audience to the museum. We... I think we've introduced it to the UK, actually.

Gemma: Yeah, no we have. I think I saw Mercedes' work at the Astrid Fernley Museum in Oslo. And she is a really remarkable artist who creates these kind of very unsettling, melancholy scenes with video but words. And like Lara said, the scripts, the protagonists of her videos, use the words are absolutely phenomenal, aren't they, Lara?

Lara: Yeah, and actually Mercedes' work, "Lament of the Fruitless Hen," and the visuals to that, I think were quite a key sort of mood for us in terms of curating the show. You know, we saw that work early on online and we kind of felt as though, yeah, this is it. It's got this "Twin Peaks" feel about it, this sort of disturbing…

Rebeka: Anthropomorphism of species... yeah yeah yes. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. I'll include a picture in the company and blog post. And oh my gosh, I could talk to you two forever. Um, and I hope that this is just the first conversation of more. I know we're over time, and I wonder just to close out if you could provide one piece of homework for the audience. I love to ask this question, like just something to think about, to consider, to look at, some kind of spell to cast, perhaps.

Lara: Yeah, I would like to suggest that everybody reads Amitav Ghosh. Um, and I've been reading The Great Derangement, and I know he's written quite a lot of things. It's called The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable.

Rebeka: I'll check that out, and that's a great reminder to read more of him. I've only read Gun Island by him, and it was just, it stayed with me. I read it during the pandemic, and it's one of the books I thought about the most. Yeah, thank you for that one. And Gemma, do you have any homework you want to add to the list?

Gemma: This is a bit of a strange one, but um, I, we, my son through my eldest son who's eight years old, he got a moth trap for his birthday last year. And I was, if anyone is able to get hold of or look at the findings from a moth trap, I kind of feel that opens up a huge world, you know, this nocturnal world that we never get to see.

And I'm saying this from London, where, you know, Southeast London, we put this moth trap out at night, and from kind of early spring right through to autumn, and it's absolutely remarkable that what is under your nose in your own environment, what you can see if you have the means to capture it is extraordinary and will give you a bigger appreciation, you know, of your position in the environment and in the world. And so that's a kind of a strange one, but if there's a means for you to get hold of one or to find out about another species that's within your own environment, I kind of feel like that gives you an understanding of your place within it.

Rebeka: Beautiful. Thank you so much, Gemma, and Laura, thank you so much again. I really hope we have a chance to connect soon. I'll share more about the exhibit in the intro or the outro, and just congratulations on what is an incredible show. I haven't seen it in person, unfortunately, but I can tell from the snippets, and I'm just so honored to have met you. Thank you.

Gemma: Thank you.

Lara: Thanks, Rebeka.

[Music]

That's all for this episode, thank you for sharing this witchy space with us. You can see photos and descriptions of some of the pieces mentioned in the podcast in a link through the show notes.

Please do get in touch if you have thoughts on witches or ideas for who should be interviewed here in this forum on art, society, and our planet. I appreciate any of your support in the form of podcast subscribing, rating, commenting, and sharing.

Thank you to Samuel Cunningham for the podcast editing and to Cosmo Sheldrake for the podcast music, which comes from his song, Pelicans We. Until next time!

[Music]