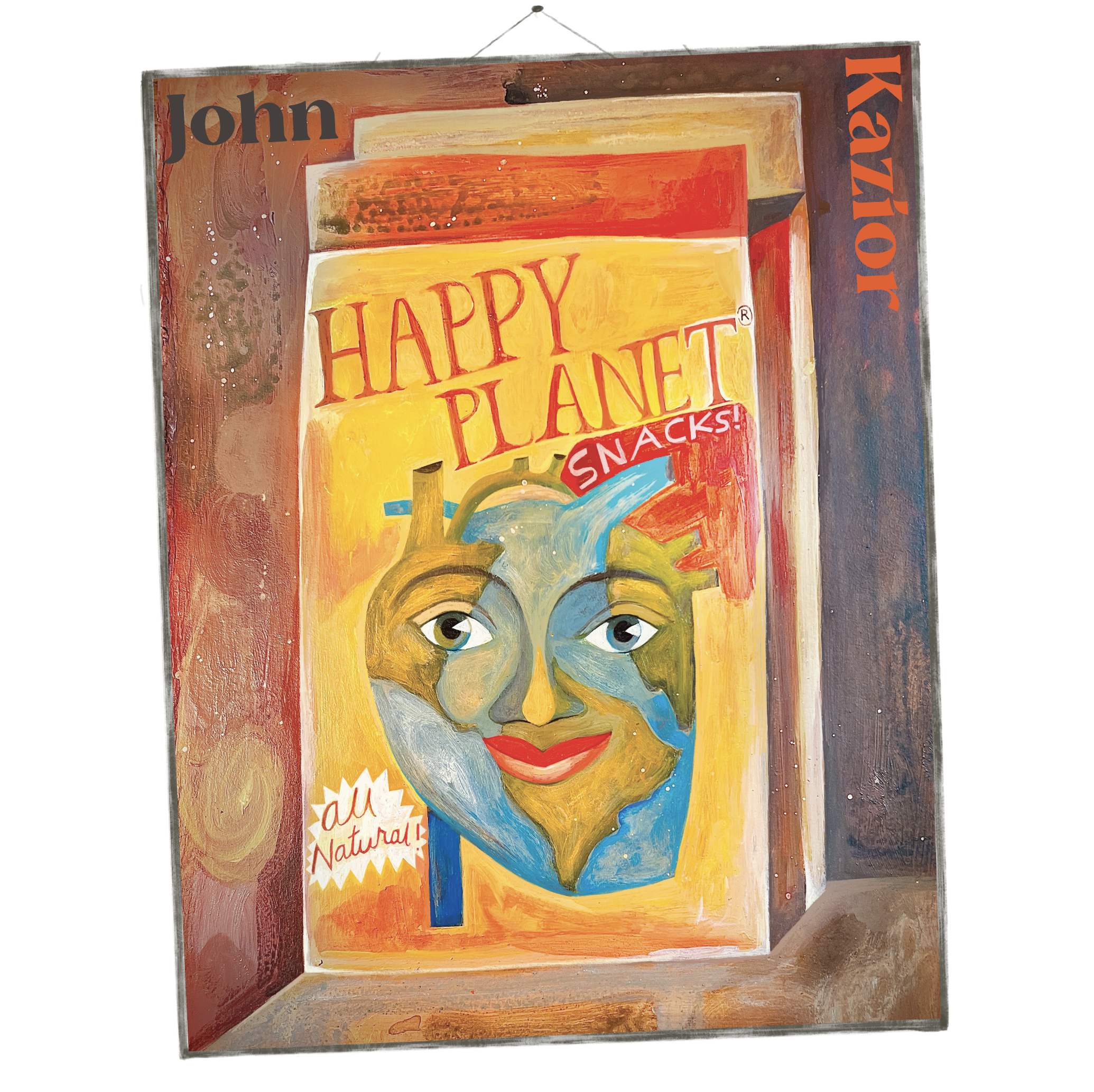

Episode 8: John Kazior on nonhuman perspectives, greenwashing arts, & moving beyond consumption

For Episode 8 of The Heart Gallery Podcast, Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer talks to writer and artist John Kazior.

On this podcast we’ve heard about art approaches that explore interrelationships between humans, nonhumans, and the environment from different perspectives and angles. We’ve heard from artists that variously raise awareness, educate, inspire connections… And that, perhaps most compelling, help spark imagination. Art can unlock new ways of looking, thinking, feeling, relating. It can help us envision and create new ways forward to a decolonized future, one that isn’t rooted in consumption, one marked by a more hopeful and alluring sense of community. Today’s guest on The Heart Gallery sparks imagination incredibly well. He is John Kazior, an American artist and writer based in Sweden.

In addition to inspiring imagination, another gift of John’s is his ability to apply an ecocritical lens to our present world. Greenwashing tactics of exploitative entities are all around us. When I started to read John’s work, it helped me see depths of the sinister behavior that surrounds us. John's writing reveals the depths of these dark arts and shares how we can come to see these efforts more clearly. He also talks about how we can learn to go deeper below the surface with issues and ideas that matter the most, and how we can come to orient ourselves towards cultures of true care. I believe that John needs to create curriculum for schools everywhere, for people of all ages. I hope you enjoy this episode.

Explore John’s writing below. The podcast transcript is also available below.

HW from John: "One good thing to do is go out and find a nonhuman species, whether it's dead or alive, a plant or fungus or a moss or a fish or a fly. Find something and try to follow it for a little while, whether that means actually physically follow it and/or [tracing its life backwards]. Follow where it came from and try and see what you can find about it. If you really want to go the extra mile, then write or draw something about how you feel about it or the way you relate to it. And that may be just reiterating like that, oh, I found this in a supermarket. It could be as simple as that. But this [activity] is something that's usually a pretty interesting thing to do in my experience.”

Some favorite artists: Petra Lilja, Nonhuman Nonsense, Brave New Alps, Climavore, & Cooking Sections.

Mentioned by John: ecofeminism, ecocriticism, entanglement, & polyphonic assemblages.

Connect with us: John: John’s website & @john_p_ark, & Rebeka: this website & @rebekaryvola.

Thank you Samuel Cunningham for podcast editing.

Thank you Cosmo Sheldrake for use of his song Pelicans We.

Podcast art by Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer.

Read John’s work:

#1: Excerpt from Every Brand Is a Climate Brand These Days, and That’s Terrible For the Environment, AIGA Eye on Design:

Illustration via article, by Beatrice Sala.

“If the growing corporate focus on climate communication hasn’t actually brought about much change since the last assessment, what is the meaning of all this climate branding? For starters, it’s great for business. Across nearly every corporate sector, sustainability-focused messaging and advertising helps move more units (especially among millennials and younger consumers). But beyond sustainability, a recent study from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication revealed that at least 40 percent of Americans have or intend to in the next year reward companies that are taking steps to reduce global warming, and the same number say they intend to punish those companies that are not. That is incentive enough for companies to get on the climate wagon. Couple that fact with Pew data that shows 72 percent of people globally are “Very/somewhat” concerned about climate change and 80 percent are willing to make changes to how they live and work to reduce global climate change, and you’ve got yourself a hot new global trend to cash in on.

Today corporate visual communication about the climate comes in many different forms, the most flimsy and uninspired among them being the corporate climate “pledge.” These promises come from big brands that aren’t quite willing to change their operations but are more than willing to sign up to emissions offsetting programs and advertise their commitment to these programs […]”

#2: Excerpt from Comunità Frizzante is Bottling a Model for Hyperlocal Food Ecologies in the Italian Alps, MOLD Magazine:

Photo via article.

“Yet for many people, it still can be difficult to wrap one’s head around the idea of a carbonated drink that isn’t mass produced by a megacorporation. A carbonated drink that is not synthesized, marketed, and sold by a single private group, but is in almost every part formed by a democratic and diverse network of people and groups. Such ideas have made marketing the full story of Comunità Frizzante no easy task. It is the character of the bottle and the beverage itself that does much of the work of communicating all that makes these drinks unique. But as every aspect of these drinks is so dependent on the community that it is being sold too, among the people of the Vallagarina valley, its radicalism is crystal clear.”

#3: Excerpt from ‘Nature-rinsing’ is the perfect term for our age of climate anxiety, Fast Company:

Image via article from Toyota.

“The arrival of a term like nature-rinsing is timely for all the worst reasons. Supran’s findings tell us not just about the endless efforts of fossil-fuel-dependent companies to deceive but also about the heightened level of climate fear many people are currently feeling. Nature-rinsing “works” best when consumers are feeling worried about the climate or ecosystem.

“Present issues such as global warming may indeed enhance consumer awareness and acceptance of the need to consume in an environmentally cognizant manner compared to other times,” says Les Carlson, a professor of marketing at the University of Nebraska who has researched green marketing since the early 1990s. “When consumers are concerned about other more pressing issues such as loss of jobs, decreasing incomes, health worries, etc., environmental product attributes may be of less interest.”

It’s no coincidence that Supran’s damning report coincided with an onslaught of news about megadroughts, record-breaking heat waves, and wildfires. The strategy deftly serves brands and corporations that are coming under increasing scrutiny for their role in the crisis. “I would hypothesize that the prominence of nature-rinsing by fossil fuel interests has increased in lockstep with public and political awareness of the climate crisis […]”

#4: Excerpt from Now Streaming: The Common Gull, Anthrovision!:

Image via article.

“Consider for a moment how much time you spend streaming entertainment on Netflix, Hulu, HBO Max, Disney+, Amazon Prime, and the rest. How many shows and movies have you watched that you don’t remember the name of? And think of how often these movies or series feel like they were written, shot, and produced by a skeleton crew of overworked and underpaid interns but also somehow still have a multi-million dollar marketing budget. We don’t live in the platinum age of television, we live in the platinum age of escaping our suffocating, isolated lives. Because the city is a harsh place to live for all of us, and in our work-obsessed, or rather, -oppressed lives no one should be forced to deal with the onslaught of humanity and machinery that we share this habitat with.

Yet we don’t need a scientific study—though there are many—to tell us that staring at a glowing rectangle for hours on end is not great for your brain chemistry. Especially when your primary function throughout the day—working—might also entail staring at a glowing rectangle. The entertainment-industry-funded egg heads in the tech industry have yet to figure out exactly how to make movies and television occur without a screen (or, a way to make live theater mobile and available everywhere—without paying more actors and artists). But with the common gull, drama is there when you need it […]”

Podcast transcript:

Note: Transcript is autogenerated.

[Music]

On this podcast, in this first season, we’ve heard about art approaches that explore interrelationships between humans, non humans, and the environment from different perspectives and angles. We’ve heard from artists that variously raise awareness, educate, inspire connections…. And that also, perhaps most compelling, spark imagination. Spark and inspire imagination and offer alternate visions about what a different trajectory for humanity and non-human creatures on this planet can look like, for what deeper interrelationships between us and our surroundings can look like. Art that unlocks new ways of looking, thinking, feeling, relating. For envisioning and creating new ways forward to a decolonized future, one that isn’t rooted in consumption, one of a more hopeful and alluring sense of community.

Today’s guest on the heart gallery sparks imagination incredibly well. He is JOhn Kazior, an American artist and writer based in Sweden. His writing has appeared in AIGA Eye On Design, Fast Company, The Baffler, Icarus Complex, and MOLD Magazine.He serves as the art director for the culture and politics magazine The Drift. He is also co founder of Feral Malmö—a project researching social-ecology in Malmö, Sweden.

In addition to sparking and inspiring imagination, another gift of John’s is his ability to apply an ecocritical lens to our present world. Greenwashing tactics of exploitative entities are all around us. These arts for deception, distraction, disconnection are everywhere, in the messaging that assaults us from politicians, celebrities, all kinds of media, products virtually we're constantly being fed messages. When I started to read John’s work, it helped me see depths of the sinister behavior that surrounds us. It’s infinitely well funded, and pervasive, and shields ncredible violence towards our environments and us as individuals and communities, and I would argue our hearts and intellects. Sounds ominous, and it is, but John in his work reveals the depths of these dark arts and shares how we can come to see these efforts more clearly. how we can learn to go deeper below the surface with issues and ideas that matter the most, and how we can come to orient ourselves towards cultures of true care.

I believe that John needs to create curriculum for schools everywhere, for people of all ages. I hope you enjoy this episode

[music]

Rebeka (00:01.048)

ominous countdown.

Rebeka (00:06.021)

Hi John, again, welcome.

John (00:07.975)

Hi Rebeka, thanks so much for having me.

Rebeka (00:12.286)

It's so nice to be with you in an official recording studio space. Welcome to Riverside. Not sponsored.

John (00:17.567)

Thank you. Yeah, it's great to be here. Yeah, it's great to be here. I'm very excited for our conversation.

Rebeka (00:26.218)

I am so excited, John, because I love what you write about so much and what you create about. You're an artist and designer and writer, and you explore topics that I find so fascinating and that I care about myself and that I explore myself. And to jump right in, I wonder if, to give you like a more specific going back in time kind of question.

Rebeka (00:54.586)

One of the perspectives you share a lot is, or one of the ideas you talk about a lot in your work, is how we can put ourselves in the position to see from the perspective of other creatures. And I wonder if you could go back in time and share how you started to experiment with that yourself.

John (01:17.891)

Yeah, that's a really great question. It's hard for me to actually recollect when that really started, or when that sort of exploration started for me. In some ways, I think everybody maybe does it a little bit. When you're young, very young as a child, you sort of like

I think it's so much easier to sort of inhabit other creatures, other things. Because you're not so in your own head when you're very young, when you're a kid. And I think for me, that was like, I was always sort of very fascinated with other creatures and other species. And it's, you know.

I think like many, many kids. And so I think I was always sort of doing it early on, but as I grew older and was sort of starting to like have my own identity as maybe as like an artist or a creative person and starting to like reflect on

John (02:45.959)

how we sort of put our own, our own interpretation on other, on non-human species and like, we sort of project so much onto them. I became more, I think I...

John (03:07.619)

I started just trying to write about other species or like drawing other species as a way of like just inhabiting those other things in very simple ways, I guess. And for me, just, you know, even if you just draw a bird or like, you know, take a moment to like look at something that you maybe don't usually look at or like think too much about or you don't really.

John (03:36.423)

consider has its own huge, you know, sort of world going on. That's totally, totally like disregarding yours, you know, or like even, or humans in general sometimes, just looking at it like other species is already a way to sort of inhabit them, inhabit their space or to like get into their perspective on the world.

John (04:05.671)

And yeah, I think, so I think it's hard for me to like say that where there's a clear point, you know, where that started. But it's been something that's like sort of evolving, I think, with me as I've grown older. And yeah, it's yeah, I think it's, it's just something that's

I think in the last few years that I've become more like...

John (04:39.307)

more aware of how I speak about it and aware of it, I guess, but I think I've sort of always been doing it in some different ways.

Rebeka (04:49.442)

Hmm Yeah, so you said that you think a lot of kids maybe do that and I wonder I mean, I don't know if that's true But I do think like one trend that I've seen is That there is a point where a lot of kids Start to be pulled

away from that and I don't have any data on this but I've seen YouTube videos and I've had many conversations about this like where for example, just to paint the picture here, where a child starts to question what it is they're eating. They start to make a connection that like, oh, this is a fish or this is a chicken, this is like the same as like the chicken that I met at the farm last weekend and they start to question. And then I feel like there's often this process where

the disconnect starts to happen. And this is specifically about animals that humans tend to eat. But I'm wondering if as you were growing up and you were having these experiences of being curious about other species, whether that was encouraged by people around you.

John (05:57.007)

I don't think it was really. I feel like for me at least growing up, it wasn't, I wasn't particularly in an, felt like I wasn't really in environments that regarded those other perspectives as important really. And I think that's something that I've only recently.

realized in a lot of ways is that like, yeah, in my family or in the environment or just in the social context I was growing up in, the things around you, like the things you eat or the insects around you or the trees, these are more or less alienated objects that sort of play, they don't really matter.

in a substantive way to like social life or cultural life. That's kind of what was being reflected upon me in that time.

Rebeka (07:07.458)

So fascinating. So where did your culture, your philosophy of caring come from then?

John (07:14.751)

It took really a long time because for me to get there, I mean, I think, yeah, as I said, I don't think I had really like, I think some people definitely like maybe grow up in environments where like they're really encouraged to look at these things and like understand how maybe how something you're eating relates to your habitat and relates to your world in a very tangible way, in a very, very real way. But

John (07:43.767)

I think for me, it came...

John (07:49.263)

I think it probably came later when I was, maybe not until even like I was in college even, I would maybe even say that I began to start to realize that this sort of.

John (08:12.383)

keeping things at this like Regarding things from a distance like that like I was sort of taught and to like keep them As objects of scrutiny, but not something that you actually It's not something that don't actually relate to your waking life in some way I sort of started to realize that that

John (08:41.822)

tied to a lot of larger global problems, I think. Like, and I think at that same time, I was becoming more critical and aware of like climate change and ecological crisis and extinction and things like this. And I think once you start to like read about those things, it just, you kind of logically come to this point where you're like, oh, there's probably something

about the way even I, like the way I think about this thing that I see every day, like pigeon that I see every day. There's probably something about that that's actually playing into this too. I think it's kind of, it became, it's like a logical point where you start to see these, you start to go into these larger issues and then you come, they come back into you in some way, I guess.

Rebeka (09:36.542)

Yeah, and you start to realize that everything you've been taught makes very little sense. Yeah.

John (09:40.491)

Yeah, exactly. And yeah, and it all. Yeah, I think, for me, it was also, I think, in like, very personal ways, like the, you know, the way that I related to other people, even though, and how other people treated me or how I treated other people. You start to understand those effects. And then when you transmit them, or like,

see the parallels in our relations to other species, then things really start to make a lot of sense. And yeah, that aspect of care becomes way more critical in thinking about these issues.

Rebeka (10:27.530)

Yeah, and in your writing, and I think in your other mediums that you work in, what you do amongst the many things that you do so well, one thing that you do so well is that I feel like you're really excellent at opening people's eyes, my eyes when I'm reading your articles, to just seeing how shallow my thinking is.

can be on certain issues, even in spaces like where I think like, oh, like I've thought about this, like, oh, my thinking is, you know, deeper than the mainstream. I've considered this, like, I feel like I'm already like a little bit on the fringe. And then I read one of your articles. Um, for example, I'm thinking about some of your climate branding. Articles or the one where you're critiquing heckle. Is that how you say his name? Ernst heckle, right?

John (11:20.339)

Yeah, yeah, I think that's right. I, you know, I hear it differently a lot. I like, I say it as heckle, I guess, but I think heckle is, I think that's right. Yeah.

Rebeka (11:22.002)

Oh, you don't agree with that one anymore. Ha!

Rebeka (11:34.262)

You have, so that article. And then there's a number of other think pieces that you have with AIGA and other publications where you're showing a part of society and you're showing like how we have come to see things is not really for the complete picture. And that's from my perspective, I'm feeling that when I'm reading through your work.

And I'm wondering if you can speak about your writing. I know you also do some non, you do some fictional writing as well, in addition to the non-fiction. And then you're an illustrator, you're a designer. What is the unifying threads through your various mediums, your various work? How would you characterize what it is you're trying to do?

John (12:21.639)

Hmm, that's a tough one, but a very good question. I think...

John (12:32.475)

I think what's really is that the heart of like all this, the different things that I try to explore or the different mediums I guess I try to explore these ideas with is that

John (12:52.755)

is I think kind of to do

John (12:58.923)

what you said in some way, to sort of pull back the photograph of the pristine vista, the mountain range, sort of look behind this photograph. And because, I mean, I...

John (13:23.675)

visual, like art and communication that deals with nature and that deals with the aesthetic of the environment or the aesthetic of the non-human nature or ecology is so powerful. It's so, everybody responds to it very easily and very like, very mostly positively, I would say, like overwhelmingly positively. People, whenever...

people are met with an image of nature as you might have, however you may describe it or think about it, people generally feel positive about it, right? And that's something that has become troubling weirdly in the world we live in now, because we now know overwhelmingly that's...

are the way we treat nature or the way we treat the environment or non-human ecology is is so different than the way we feel about it in some way and and yeah it yeah it's it's become there's a there's sort of this huge growing ontological or rift between

Rebeka (14:37.846)

Can you share more about that disconnect?

John (14:52.519)

The world we see, the nature that we see in products, the nature we see in advertising, the nature we see in even photography on Instagram, on what we see in social media, what we see in all the material that is produced to advertise, market, or even just communicate a message. All of this material creates, it uses nature.

and uses an idea of nature, creates a feeling around nature, and does it with such power and rapidity that it almost, in some ways, blocks out the world, the very real world around us, right? Like the nature that surrounds us every day and the environment in the species that surround us every day.

John (15:52.443)

we are increasingly alienated from the climate, from ecology. And the result of that, of course, is these things are being destroyed and going extinct. And the climate is getting warmer and warmer and there's no sign of it stopping. And it's become, whereas sort of nature as an image

John (16:22.735)

was maybe some time ago, sort of just a banal thing that we see maybe on the postcard or on television. It now becomes an almost...

John (16:40.683)

different, it becomes a different reality and it becomes kind of a destructive reality when we start to see it in these things. And I think that's kind of the interesting tension for me, is that

Rebeka (16:53.822)

Yeah, John, I wonder if you could share some examples. And just before you do, I think I can't remember if this was in one of your pieces of writing or if this was in some talk that I heard you give, but you talk about garbage. This is like some of the language they use. It's so beautiful. Garbage as a species. You talk about beautifully designed waste. You talk about the supremacy of objects. And like just to illustrate this point that you're trying to make.

between this marketing design, I would say even artistic reality that we're being fed around consumption and the disconnect between that and our local realities, our ecosystems. Can you share some more, some examples about what that looks like?

John (17:45.679)

Yeah, I think, for example, I guess a story that I wrote relatively recently was about this new term, nature rinsing, which a professor from Harvard coined sometime last year in this

John (18:15.491)

advertising for fossil fuel companies and car companies and airlines. And how these things that are so these companies and these corporations that are so overwhelmingly antagonistic towards ecology and towards the climate have this, have this

digital online presence, this media presence that is superlative in its expression of nature. It uses images of other species of sharks and sea turtles and they use all these beautiful

John (19:13.055)

sort of these classic sort of travel depictions of, you know, certain regions in a very like hyper-idealized ecological way. And it's very like, it feels, I mean, if you look at it twice, you see how artificial it feels in some way.

Rebeka (19:35.394)

What a weird, yeah, what a weird psychological trip. And I think you're getting at something interesting there by saying like, if you look at it twice, because I think what that says is that they're expecting, and this is rampant, right? This is everywhere. They're expecting that no one is looking at it twice, right?

John (19:38.743)

Yeah.

John (19:52.759)

Yeah, and that's part of what makes it so difficult to compete with, for anybody. For even the most hypercritical person, it's very, very difficult to have the mental capacity to take the time to look twice at these things, you know, because there's so much.

There's so much being produced, especially in the digital, increasingly in digital spaces. It's been discovered how sort of rapacious sharing these kinds of nature images can be because you can produce so many of them. You can put so many of them out that nobody has the time to go back, go back two posts or think about it.

Rebeka (20:31.232)

Yeah.

John (20:48.903)

you're just constantly being sort of bombarded with it. And when it comes at you in that way, and when you consume it in that way, you obviously, you can't, like, no one can be expected to be like, well, this is, you know, I should really think twice about this post, this random post, because it's clearly a deception, or it's clearly trying to deceive my understanding of what this,

terrible company is, you know. Um, so I think that's like a peculiar, uh, I think, I mean, a very recent, and, uh, it's very distressing, but also very interesting example of how, um, sort of suffused everything is with this, this strategy, this tactic of, uh, using

John (21:45.895)

these conflicting ideas or images of nature and ecology to sort of numb or block out or distort the very obvious awareness that most people have that this is not how the world looks actually right now. And it's not going to look like this certainly for very much longer maybe.

Rebeka (22:14.474)

Yeah, and I think it's that one of the tension or this tension that I feel when I read some of your work is that on one hand, I'm so grateful that you're raising my awareness to whatever it is, the issue that you're bringing up in a given piece. And then on the other hand, I feel like, how is this going to, like, how are we going to bring about this way of looking, of like deeper looking, of being more critical, critical thinking?

Rebeka (22:44.594)

You talk about eco-criticism, like how do we instill this as a cultural movement? And I want to just share one example before I ask for your response. You wrote an article about this invasive, quote unquote invasive species, actually a group of species, and there's like four carp species that are present in the Midwest. And I can't remember all the names.

Rebeka (23:11.694)

and they're just taking over ecosystems, driving other species to extinction or to fringes of ecosystems. And there was this, I mean, I'm probably getting this wrong, some fishery service ministry governmental entity hired a branding company to come up with a brand, to rebrand, to rebrand this group of carps into a copie coming from Copius.

So they came up with this whole branding strategy showing like, oh, this is a wonderful, delicious fish. We should all be eating this, like beautiful design. And you wrote this article showing many issues with this whole effort to control this, quote unquote control this, quote unquote invasive species, which I'd love for you to talk about. And yet there are so many other articles that I saw that were not going.

deep like you, that we're saying like, oh, this is an excellent way to control a species, look at this huge success story, look at how this can work, like really reputable agencies, entities, news sources, we're talking about how this is a really great thing. And then you come in and you're saying, well, like, okay, but wait a minute, like you guys are a surface level and this is the actual issue at play. So I wonder if you could talk about like what was, what the narrative is around this because I missed some pieces, maybe misrepresented.

And then if you could talk about like how we break out of this surface level thinking that is just everywhere.

John (24:45.219)

Yeah, it was a super interesting story and one that I really, yeah, I really enjoyed writing but it's, it is like a really, it's a very tricky topic, especially I think with invasive species. But yeah, what, yeah, I think you described it quite well in general that that's this company. Yeah, rebranded this.

John (25:13.211)

what's known as commonly referred to as the Asian carp, as this invasive Asian carp that lives in the Mississippi, was brought here by, was brought to the US by catfish fisheries, farming, or catfish farmers basically, to sort of clean up the water for these catfish.

in these fisheries and because they eat, whereas catfish are bottom dwellers and they sort of eat things on the riverbed. These particular species of carp, there's four, as he said, they are surface feeders, so they eat things at the top. And so they were perfect, you know.

John (26:08.871)

for cleaning up the water. That was their view, the view of this fish industry at the time. And of course, they got out through flooding. They entered the Mississippi and have spread like crazy. They've really taken over the ecosystem of the Mississippi and some of the surrounding waterways. And they have, for the last few years, sort of been at the...

precipice of entering the Great Lakes. I think they have been spotted in the Great Lakes already, but they have yet to spread. But this would basically be a catastrophe for the fishing industry, the multi-billion dollar fishing industry in the Great Lakes, because they would really take over the ecosystem.

John (27:06.775)

They, and the other, of course, the other complexity of it is that they, these carp do destroy, you know, the, in some ways, they destroy the habitat for other species because, you know, they're new and they have, they just, it's, the rivers have not been adapted to it, the other species have not been adapted to it, so of course, it's a problem, you know, but...

John (27:36.099)

I think, I mean, that's the interesting thing about that story and like what you were saying about how there's all these other articles that were saying, oh, how great this is that like, this is a way of dealing with the carp, right, that we can like rebrand them and this will get more people to eat them.

theoretically, which is strategy, but that's been tried many times before. Though this, I guess, is a more sleek sort of like high, uh, yeah, high design sort of attempt at rebranding, uh, the carp in Illinois specifically. Um, as Coppi, uh, but the thing about, I mean, the thing you see often, I think when

John (28:29.607)

with reporting about invasive species or other species like this is that there tends to be this idea that these species, invasive or otherwise, but particularly with invasive species, so-called invasive species, is that these things do not have a history. They don't have a relationship to.

John (28:57.191)

society they don't really i mean they're just sort of like they get that they're very easy to sort of black market's these past right there's likely sort of things that are destroying are ecosystem and that's bad you know it's very black and white uh... and it's very easy to do that because of course carps have no representatives coming up and saying like a this is not uh... not fair to just be

Rebeka (29:21.471)

Hehehehe

Rebeka (29:26.614)

They didn't ask to be here.

John (29:28.191)

Exactly. And it's, and it's also, yeah, of course, with the, the language of calling them invasive species is also very strange because, well, we brought them here, the fishing industry brought them. It's not like they came in spaceships and invaded the country, you know, it wasn't, they're not aliens, extraterrestrials, they lived somewhere, they had their own habitat, and we brought them for artificial reasons, for economic reasons, to, to

Rebeka (29:43.566)

No.

John (29:57.739)

improve our fish industry. And, and now they are a problem, of course. That's, and that, you know, that's what tends to happen when you move species from different places, artificially and expect, you know, everything to be okay. It usually turns out pretty bad, especially if it's a particularly tenacious species like these carp.

John (30:26.643)

And so it's, I think, yeah, it's, it's just so easy to not think too hard about other species, I think, for a lot of sort of more classic reporting or like writing about these things. And, and, you know, with the Kopi story, it is like,

John (30:57.383)

I mean, it's not to say that like eating these fish or maybe finding a new way to like, adapt them to our culture or society of this particular space, especially in the Mississippi region or in regions where these carp exist. It's not to say to try and do that is bad or wrong, but we should be.

John (31:25.987)

accurate in the way or we should be we should try and dig up why this is happening in an honest way and like why how did it get to this and is it really like just that these carp are so terrible like is it that simple and usually it's not and uh and i mean i think especially i think uh with this story also is of course the other side of it is it was it's an extremely aesthetic facing story it's about the new

about the branding of this fish, which becomes another way of abstracting the history and the ecology behind this fish, because it flattens it, right? It flattens it into a product, whereas the invasive carp is a terrible, unsustainable fish.

Kopi is a very sustainable fish, you know, just that's in this different form. And those sort of things that brand, in that sort of situation, branding starts to serve as like a wall against, a wall between us and these species. And I think it's, yeah, I mean, I think it's just hard to.

John (32:52.268)

You know, I think reporting on that, it's...

John (32:58.551)

or like writing about that particular story, it's not, it's easier to think about the aesthetic, I guess. And it's harder, you know, it takes, it's a bit harder to go deeper into those things. And yeah, it's tough, I mean, I guess.

Rebeka (33:15.774)

Yeah, what's your hope? I think this is something you spend time thinking about. Here you are doing this excellent work, showing the ways in which our imaginations are failing us, our critical thinking is not there. You're raising specific issues and helping show step-by-step like where those things are falling by the wayside.

Rebeka (33:44.114)

And yet we continue to have these hugely powerful corporations, you know, with this hugely toxic, awful messaging that just like looks so sleek and nice. And we continue to look for the soundbite media. We continue to scroll really quickly. We continue to just accept things as fact. When it just like flies past on our screen, like what are you hoping? How can we get out of this?

John (34:16.253)

That's the big question. How can we get out of this? Yeah, it's a very good question.

John (34:28.569)

The tough thing is, you know...

John (34:36.148)

We, as individuals who are looking at this stuff, we on our own, you know, there's really no way to get out of it. There's no, you know, you can be the most critical person in the world and be, you know, super knowledgeable about everything or just very, very aware, but of...

John (35:03.015)

of like sort of these issues, you know, and whether it's greenwashing or just, you know, with how media works. But it's still, we still face pretty much this huge power dynamic, right? Where sort of like with the nature washing story about like how like a fossil fuel company

has so much, so much, so many resources and so much money and so much creative talent and so much behind it to be able to just produce these messages constantly, like through night and day, you know, it's no problem for them. It's nothing for them. And it's the same for every other, you know, industry. That's sort of.

John (36:03.091)

same for every other like very powerful multinational industry. They have such access to us, you know, they have so many ways of reaching our eyes and ears and they can do it constantly and nobody can fight again. I mean, nobody can, I mean, I, I know I can't like compete with that, right? That I can't just stop in some way. But for me.

I think the hope I have is that more people start to, and I think this is happening, is that more people start to look to the people around them for...

John (36:53.783)

not only for knowledge, but for how to treat, you know, their environment, how to treat each other, how to care for each other. Because that's always going to be, you know, like, it's always, you're always going to have more ability or more power to fight against something if you have another person next to you who's who, who sort of like is

is also there with you. And I think that's sort of something that has to be done, that we have to be more conscious of people around us. And even if we do use social media, or likes are still, and it's pretty much impossible not to use social media now because so many people's jobs and lives depend upon it.

John (37:49.471)

You know, you have to, it's a part of our society and you can't, most people can't just unplug from these things or like sort of drop out of these things now at this point if they want to, you know, be able to have a job and a livelihood. But we can still talk to each other and, you know, and like form, you know, relationships with each other and communities around these

John (38:20.155)

these ideas of justice and critical thought. And I think if we start to do that, start to talk to each other and start to build, start to reinforce these narratives and distribute them amongst ourselves, there's hope that we can begin to fight these things, right? And begin to shift.

John (38:50.619)

to compete with that power and to sort of demands more regulation against sort of this sort of control over communication or media or distribution of images. You know, it's not, I don't think it's, I mean, I would like to say it's, you know, you can just be really well read and you can just be critical and you'll be fine. But like.

John (39:20.527)

I don't think that's the case. I think you need to work with other people to fight against these things. And I think that's, you know, at least I think that's the best chance we got at competing with these things and being more and taking away power from these absurd powers that fossil fuel companies have or car companies have that they can just completely...

John (39:49.319)

dominate the things we see and like our understanding of nature every day. It's I think Yeah, by working with people around you that's probably going to be the best way to To start the fight piece

Rebeka (40:07.402)

Yeah, and I know you also, in addition to raising awareness of some of these sinister arts and design tactics of these corporations and even government and other entities, you also share about art and design and storytelling to do the reverse, right? To help us connect, to taking it back to the start of this conversation, to help us potentially see...

a perspective of a completely different species who we might have never even noticed before. And so I wonder if you can speak about some of your some of the efforts that you're excited about in that realm, like where some of these very big and powerful efforts on the part of these sinister entities are being countered, maybe in a smaller way, but I would say also in a powerful way with with these more.

ecologically focused, non-human centered perspectives and thinking about like art design story so forth.

John (41:12.919)

Yeah, I think there's a lot of great stuff happening. And one thing, one, I guess, example I might name that's maybe more specifically confrontational against these in a very little way against sort of fossil fuel greenwashing advertising is the group known as Brandelism from the UK.

Rebeka (41:39.815)

Don't know them.

John (41:40.923)

Where they do these greats, I mean, they basically like take over billboards in the UK and like sort of make these parody car advertisements and like just ads for like all sorts of companies that are like, you know, focus on basically calling out greenwashing and they do a really, really great job and I think it's a very.

John (42:10.895)

It's very visible, it's very creative, and it's very like, I think it's, it's very effective in sort of pointing to the absurdity of, of like car advertisement or seeing car advertisements in a climate crisis, you know, like it's, like they, like.

Rebeka (42:27.614)

Always like this one car in this most majestic landscape. The only car in the universe.

John (42:31.091)

Exactly. Yeah. Yeah, exactly. They so I think that group is definitely one I would say who is like really using creativity and like art and design to go directly against this sort of messaging, which I think is very effective in its own way. And I think it's Yeah, I think what they're doing is great. And there's also

John (43:00.859)

One artist duo I would highlight as doing really great work right now in this sort of, especially in the realm of like thinking about non-human nature as it relates to, relates to people and how it relates to society, how other species relate to society, the group called Cooking Sections.

John (43:29.615)

They, I'm really a big fan of their work. They've done a couple, their most recent exhibition, which has been sort of, it was at, I think it was at the Tate Modern in London, but also has been sort of traveling around Europe, I think, is about salmon and the salmon industry and about how the color of salmon is, you know.

John (44:00.071)

basically artificial the way we see it in supermarkets now. And there's this like really, I mean, they do a great job of sort of like dissecting how this visual indicator of like this thing we know is like, is a sign of this, you know, like sort of anthropocentric ecosystem that we now.

Rebeka (44:04.640)

Right.

John (44:27.791)

live in, you know, and it's about how the disruption of salmon life cycles due to farming is causing their bodies to physically change, the color of their bodies is changing. Now mostly, like most of the supermarket salmon you would buy actually is white, it's flesh, they're like colorless, I guess. And they use this special like pigments to basically color.

the salmon colored, you know. And cooking sections, they've done a lot of other great work about urban trees and yeah, and they're doing another project about eating in the climate crisis and how we change our diets about, and I think they do really fantastic work. And I think another group I might just...

It's a little bit more of an education institution, but they do also work with art and creativity as the Institute for Post-Natural Studies out in Madrid. They have a lot of seminars about sort of critical ecological thoughts, but they also have a lot of exhibitions featuring, you know, a lot of...

new ways of, or different ways of looking at other species and how technology figures into our understanding of species, other species today and, and, and ecology. And I would shout them out, shout them out as well because they're doing really fantastic stuff. And yeah.

Rebeka (46:15.982)

That's great. That's great, I'll link all those. And I wonder if, just thinking about all of the greenwashing, you're mentioning greenwashing quite a bit. I'm wondering if you have any advice, any process that maybe you go through or that you have shared with others before on how to identify greenwashing? Because reading through some of your work, there are some, you share about, for example, some smaller brands, you talked about this, for example, a local beer brand, I can't remember where they.

were located that was, it was doing quite a bit to counter their environmental and climate impact. And, you know, then you go up to the bigger brands and it's like the greenwashing just becomes like more obvious, I think, oftentimes, and obviously way more egregious when we're talking about these big scales. But like, how can people start to notice greenwashing? Like, what are some quick tips?

John (47:12.047)

Yeah, it's really tough. I think in general, just being aware of when brands start talking about environment, like the climate or environmentalism. I think once that starts happening, you should immediately begin to be like a little bit

skeptical in general because something I've written about a bit is about how the emergence of brands embracing their climate profile or their carbon footprints or these net zero policies. The embrace of these things, these concepts and like...

John (48:09.343)

In many ways, marketing tools are a way of getting ahead of the fact that people are starting to realize that there's a problem with the environment. More and more people start to realize that climate crisis is really a problem and it's starting to affect more people. This is a way of getting out ahead of that, is to say that would go well.

Rebeka (48:32.402)

But also to create this sense of trust and assurance. I can imagine that for people who are starting to have these anxieties or have had them for some time, seeing that some brand, corporation, agency, politician, whoever, that they're talking about it using the language.

John (48:40.561)

Yeah.

Rebeka (48:57.430)

that you can just sort of be lulled into this sense of complacency. Like, oh, OK, I don't have to ask any more questions. I don't have to investigate. So seeing beyond that, it seems like it's a huge challenge.

John (49:08.587)

Yeah, definitely. And I think that's also, it's a really great point because also, I think, you know, something that's really dubious about, you know, environmental or climate branding or messaging or green and greenwashing in these forms is that it tries to

John (49:37.691)

It does a little work to try and, you know, feed off of your anxiety or guilt or fear in different ways. And the really terrible thing is it ties it to capital, you know, and by consumerism. But it's one thing I think is good in general to sort of be more aware of.

John (50:06.975)

greenwashing, looking at it this way, is to not try and, don't try and seek, you know, some comfort from products. That's one thing I'd say. Don't try and, you know, find some environmental or ecological harmony from buying something. That's generally, that's a bad path to walk down.

Rebeka (50:27.958)

Hmm, that's so good. That's so good.

John (50:32.803)

say. And that's when it becomes really difficult to get unentangled, disentangled from greenwashing. Because once you start to see it as something that's actually connected to the way you sort of feel about the climate or you feel about your own relationship to the environment,

then it's really hard to get out. And it's really hard to see where the walls are because with so many things, I think, you know, if it's like a smaller company, a smaller, you know, or business, you know, I think in general, you can at least like do a little bit of work to, you can like sort of, or if you can like talk to the person who like works at the business or something, you can sort of get a sense of like, okay, I can sort of see.

this product. I can see where it comes from in some way. I can sort of, you have a closer sense of it. But with any product that's like made by a multinational, you know, huge supply chain company, there's always this huge opaque thing that you have to try and decipher meaning out of. If you want to like really try and analyze its ecological footprint or its relationship to

the many, many places and people that it affects. So you're gonna be spending your whole life doing that. So I think those would be my tips in general.

Rebeka (52:10.658)

That's such a good tip. That's such a good tip. And you wrote somewhere about going from this technologic to ecologic worldview. And when I was reading that, I was thinking about this whole idea of like conscious consumerism and just how flawed that is, right? And how it's become so normalized that I think that there is this very dominant sense that like we just have to go from being destructive consumers to conscious consumers. And

What's not happening in the mainstream is exactly this. We're not talking about how we become not consumers and how we become, I don't know, what should we be replacing them with? Is that like being conscious community members? Like is that, I mean, looking at some of your work, especially the community work that you're doing with Feral, is it Malmo? I actually don't, I've never said that name aloud. Malmo.

John (53:01.883)

Yeah, mama, yeah.

Rebeka (53:05.002)

With Fairall Melmo, I feel like you're maybe getting at that idea of like you're finding, you're not just saying like no, consumerism as a whole, conscious or not, is bad. You're saying this is the alternative. Can you talk more about maybe that initiative and whether you think that's true?

John (53:21.883)

Yeah, I think it's at least an attempt to try and sort of find the alternative to that, I guess. Yeah, I don't know if we've really cracked it yet, but we're trying to, I think it is, the project itself is more or less just about, to briefly describe it as, is just about

John (53:52.315)

you know, trying to get people together within the city, people who live in the city or even who just are visiting people who have some familiarity with the city, bringing them together and trying to just talk about the things, talk about how ecology figures into our life and trying just

point out these relationships more than anything, like try and identify these relationships, whether that means the relationship to the trees in our neighborhood, streets, like looking at them and thinking about why are they there? Are they healthy? Like, what is the point of them? Where were they before? Where are they going? These sort of questions, and also, or also about like...

Why is it that we have, you know, all these types of fish in the supermarket, but you know, there's a huge crisis in the Baltic Sea related to fishing stocks and the depletion of fish populations. Like why, why do we still have this? The, and why do we have these other species that aren't even from?

you know, close regions and the supermarkets, uh, and, and how did they get here and where are they going? You know, uh, sort of like, so it's, it's really, yeah, it's just about getting, I think for us, it's, it's about trying to really see, uh, ecology in our society, ecology in our city, in our neighborhood, in our community. Because

John (55:47.567)

There's so much, yeah, as we've been talking about, what we see in greenwashing and brand communication about the climate or ecology, these are all abstractions of climate of other species. Their interpretations and messages that come from...

places of various origin, and they sort of create this fog of ideas about what ecology is, what actually is the problem, why are we having a climate crisis, why are species going extinct. It clouds these connections, it clouds these thoughts. And I think for us with Faro Ma'ama, we want to...

Rebeka (56:40.288)

Yeah.

John (56:47.815)

We want to clarify them. We want to bring some lucidity to the way we actually do connect to other species. Where we see them, how we see them, why they are transported across the planet, why are there invasive species? Why are local species better than invasive species? Why are some species that are here, but aren't?

native necessarily, but also aren't labeled invasive, what's their deal? Why are they not bad but not good? It's just that there's so many things you can look at just around your corner in the supermarket. There's so many things you can look at and start to follow these threads. This is where you learn the most about ecology.

Rebeka (57:34.004)

Yeah.

John (57:43.143)

you know, and how it relates to society, because it's, you see all the forces that are moving species that are, that are moving resources, that are moving minerals, you start to see how they're all feeding into these, these, these systems, these infrastructures that we have, whether it's food systems or energy or, you know, and you, once you start to see these things for in there, in their

reality or in the real form or they're in a very tangible way. It's much easier to sort of.

John (58:21.767)

I think understand ecology more and to understand why we're having so many problems and understand why greenwashing is very problematic.

Rebeka (58:36.406)

That's excellent. And just, if I could ask you a couple more questions, I know we're over time. One thing I really wanted you to touch on is, some of these topics can feel quite esoteric. Even just like when I was researching you and reading your materials ahead of time, I had to look up a lot of terminology. I read about eco-criticism and that was great. I learned a lot.

John (58:42.299)

No, no.

Rebeka (59:06.682)

Um, and I'm wondering though, like with, with this esoteric nature of some of these topics, um, on one hand, and then on the other hand, a lot of the issues that you're talking about have so much to do with every person, right? You're talking like, I, I read an article about, um, that you wrote about seed banks versus seed libraries and

how we have these, we've long had these things called seed banks in the world where seeds are sealed in these like deep vaults where like in case like there's global catastrophe, which like there is, we will have these seeds stored away and you talk about like how this is really problematic because well actually like we have food crises everywhere and we've lost like somewhere between like 80 and 90% of crop varieties in the United States and.

Rebeka (59:57.974)

What we need is seed libraries where anyone can go and access seeds that can grow in a given environment, in a given piece of land, in urban areas, and people can go educate themselves on how to grow those things. But I'm wondering, like, what you think about, like, a lot of this conversation is happening in these academic esoteric spaces, when in fact you're talking about issues that have to do with people who are maybe not

in those spaces? How are you navigating that?

John (01:00:30.143)

Yeah, that's a really great question and a really big, big challenge, I think, for, or I think it's something that I've really had to, you know, I'm still really working on and I don't know if I've really figured it out yet. But I think that is, you know, something that I think about a lot in general is like the way that some of these ideas are.

John (01:01:00.559)

I came to them a lot from academic texts or theoretical texts that are very... Yeah, they're hard to read and they're very good and they give us a lot of information. But they are a specific way of communicating, of course. And they're kind of like...

very reserved for certain spaces, you know, certain, whether it's an academic space or like certain cultural spaces and they don't do much good when they're, when you're trying to talk to a lot of people or just somebody who hasn't taken the same courses as you and like critical ecological thought, you know, like you can't just like, you know.

Rebeka (01:01:50.920)

Yeah.

John (01:01:54.227)

dropped those terms in casual conversation and it's not really it doesn't do anybody any good you know especially if you're not if you're not a teacher or professor like you're not and you don't you can't expect people to be like sit through a lecture on or you can expect everybody to sit through a lecture on some really deep uh... theoretical ecological concept or whatever but uh...

Rebeka (01:02:02.124)

Hehehe

John (01:02:24.019)

So I think so the way I think I've been trying to I think I've been trying to work on my own you know language in general about like in the ways I write like trying to be more but also trying to be more trying to find better metaphors for talking about these things and better ways of like telling these stories and I think that

John (01:02:54.099)

It's something that also with like Farrell that we are confronting a lot because we're trying to like communicate about, I think in the beginning really we were like, we can talk about like ecofeminism concepts, like entanglement and like all these things or like polyphonic assemblages and all these like really specific anthropological like, yeah, these like specific terms.

Rebeka (01:03:13.294)

I'm sorry.

Rebeka (01:03:16.534)

We'll include those definitions in the show notes.

John (01:03:20.731)

that nobody, no, like nobody understands, but we're trying to like make workshops. So, but yeah, it's, it's, it becomes like, yeah, it doesn't really do much. So, I mean, I think, but the good thing about like this, these topics and topics around, uh, you know, our ecosystem is that actually most people.

John (01:03:49.027)

I think, or in my experience, most people are pretty, it's pretty easy for people to understand things that are, you know, like tree, like, you know, everybody has a relationship to a tree in some capacity, right? Like they know about trees, they probably have a tree in their neighborhood or like, you know, they, there's all of these things are very familiar to us in, in,

And the ideas, these big ideas, these critical ideas, they don't necessarily have to be cooked up in these grand ways, but they can just be expressed in very simple connections and simple relationships to a tree or to a plant or to a bird. They can be, you can still teach these things by just, or talk about these things by just talking about...

Rebeka (01:04:35.214)

Totally.

John (01:04:49.020)

Yeah, why there's only a few specific species of birds that live in the neighborhood? Like, why is it this way? And we can, from there, we're like, yeah, in this neighborhood, from there we can start to talk about, okay, how do these birds, like, what's your experience like in seeing these birds? Where they nest? Like, how do they?

how are they living? And sort of like, I think just like sort of unwrapping these connections to other species has been the best way for me to sort of get more people interested or like more, bring more understanding to these ideas because eventually when you just start to talk about the narratives of like rats or hedgehogs in the area, you start to understand that like.

Rebeka (01:05:34.123)

Yeah.

John (01:05:46.459)

Ah, there's some relationship to urban infrastructure here, right? Like rats thrive in a specific urban infrastructure, but other species don't. Right. And why, and maybe because, you know, there's more money put into property in the city and more urban infrastructure built around these urban centers, we can start to talk about how capital begins to affect, you know.

your ecosystem and we can start to talk about how history, how a history of a place, a cultural history of a place has impacted the things living around you. They have impacted why there's ginkgo trees on every street in most cities. You know, like why is this ancient tree so popular?

John (01:06:46.371)

moving from the very deep academic theoretical terms into these more stories and narratives and history into these things that everybody sort of understands in some way and has their own reflection of or own interpretation of, I think has been the best way to sort of bring more people into it. And I don't.

Rebeka (01:07:15.425)

Yeah, like...

John (01:07:16.035)

I don't think I've mastered, you know, I wouldn't say I'm probably, I'm not maybe the right person to ask either. I like, I think I'm doing my best to try and talk to more people, but like it's, and I'm trying to learn more how to talk to, talk to more people about these things. And, but those are the strategies that I've slowly been, you know, figuring out.

Rebeka (01:07:40.646)

Yeah, creativity and storytelling and some of your pieces are directly doing that, like your creative writing, the piece you wrote about, Germanators, and then there's this common Gaal short piece. And I'd love to link a couple, a little excerpt from each of those, because I think those are two excellent examples of how through creative storytelling, you are just offering a little bit of a...

Rebeka (01:08:08.438)

different perspective for people to see their surroundings differently.

John (01:08:14.519)

Yeah, and I think like with the fiction writing has been, yeah, something that's, I mean, I'm trying, I think I'm trying to bring in these ideas as best I can. It's, it's, you know, I don't know, without, you know, I don't know how effective it is always, but I think the interesting thing about writing fiction, for example, about other species or like about the environment in the city or something is that

you can really start to like talk about the way, or you can really start to explore the way people feel about other species and the way you feel about other species, right? Like, you know, whether you hate rats or seagulls or, you know, like I live in like in Malmo here where I live, people really hate seagulls because they're everywhere and they're very loud and they have, you know,

John (01:09:13.607)

They're very aggressive and you know, they're pretty big also, you know, and like, uh, and I love them because they, I love that they bring out such like, I mean, it's not great that it's always hostility that they bring out in people, but I think it's, I think it's super interesting that people have such emotion connected to a species, which is pretty rare actually. Uh, that's, you know, you get such.

Rebeka (01:09:30.627)

Nyeh.

John (01:09:42.415)

you know, like really passionate feelings about something. And I think, yeah.

Rebeka (01:09:46.646)

Oh, that's so interesting. Yeah, and I didn't realize that reading that piece, I mean, the piece is beautiful and that makes me love it even more. I didn't realize that there was such a strong passion, negative passion towards goals. And it makes me think of this rat podcast. It was a through line episode that I listened to recently about rats and about how similar rat behavior is to human behavior and how we've co-evolved in these incredible ways. And we all so.

as humanity. I love rats, but we love to hate rats as well. And yet, like here we are living with them. They're living with us because we're just so similar to them.

John (01:10:24.699)

Yeah, exactly. It's really fast. I mean, for me, those are always the most exciting species to talk about and think about because they're just those really annoying ones. The ones that really get under people's skin and really bring out... And the thing is, the other interesting thing about...

John (01:10:51.663)

rats and seagulls and pests as they're, you know, as we call them, is that they get the most emotion out of us. And, but, but we also don't really, you know, there's, there's no like parallel, or there's very few parallels where people feel the same level of emotion, but in a positive way towards species. You know, people like

Rebeka (01:11:17.814)

What do you think those are? Like whales maybe?

John (01:11:19.659)

Maybe, yeah, maybe like the ones that have been turned into sort of brand mascots, the like, yeah, eagles and pandas and blue whales and yeah, I mean, but I would even say that people don't have, I mean, people like those animals a lot. Well, okay, I want to revise and say people love dogs, of course, and people love...

Rebeka (01:11:26.210)

Like eagles. Yeah.

Rebeka (01:11:33.270)

You're right, there's so few that I can think of.

John (01:11:49.171)

People love cats, I guess, too. But, yeah, but these are largely species that have been so, yeah, like anthropomorphized, or they have become extensions of humans in some way on their own now, and that's maybe why we reserve so much emotion for them. But, but yeah, I, I'm.

Rebeka (01:11:51.766)

Sometimes. It's also, it's either, yeah, it's one way or the other.

Rebeka (01:12:15.042)

Dogs and cats are funny. I feel like the cats are more divisive than dogs because cats have their own opinions and lives. I think more than like the dog stereotype, right? Like we don't want to feel like we're insignificant to a creature, but you know, cats are much more likely to make us feel that way than a dog. Yeah.

John (01:12:24.965)

Yeah.

John (01:12:33.611)

Yeah, yeah. I think there's also something very much about, I think people, I get the sense that a lot of people at least in like, yeah, I mean, don't really love species that are willful and independent, you know, like cats. Cats are the exception because people do like them. But, but dogs are so much better because they're, they're kind of coded.

Rebeka (01:12:55.770)

Yeah, so much. Oh, so much. They need us so much. Yeah. And they missed us so much. Yeah, when we leave. Oh, it's so true. John, just to bring this around, back to the beginning where we were talking about design and art, I mentioned to you that thanks to you, I learned about...

John (01:13:00.431)

in some way and they love you and they need us. Yeah, it's like, okay. Yeah, exactly. Exactly.

Rebeka (01:13:25.422)

pollinator artwork and also just this idea of, which I'd never heard before, this idea of creating art and or designing for a creature, for other creatures. I learned about pollinator artwork through you, like this idea of like creating like beautiful gardens for the enjoyment, not of humans, but of pollinators. And to close out, I wonder if you could share.

John (01:13:27.002)

Mm.

Rebeka (01:13:55.054)

some of your favorite artists working in some of these spaces that we talked about, or creations, or even design work, but just some of your favorites.

John (01:14:08.119)

Yeah, hmm, this, that's a good question. It's tricky because I think there's, it's a bit of a emergent, I mean, the sort of art and design that's coming out of that movement for non-human sort of, non-human nature and...

John (01:14:38.711)

design that sort of serves other species is very, it's very new and exciting and interesting and it goes into so many different directions. And I think, like you're saying, the pollinator gardens I think is a really great example of, you know, it's tricky because

John (01:15:06.619)

It's hard to design things for other species, right? Because it's, you know, you don't know, we can't know what other species feel about something. And I think like the pollinator designs I think are really interesting because they begin to sort of, they begin to consider why.

or like how we might like sort of structure things or design things or create things in such a way that other species can get some enjoyment out of them. And I don't think there's...

John (01:15:43.615)

I'm trying to think of another good example. Like that's.

Rebeka (01:15:50.484)

Any art, any art and design that, or artists, creators, that you're excited about these days.

John (01:15:58.483)

Um, I think, so there's this group here in, well, a few Swedish artists that I can talk about that I've gotten to know over the past couple of years for sure. Uh, is, um, I've been working with, uh, or working with this artist a little bit, uh, here in Sweden, her name is Petra Lydia and she is, she's been, um, she's a designer, uh, she's product designer in her background, but she's been working.

John (01:16:28.635)

with, there's in the city of Mammoth, there's this old quarry, this limestone quarry that is no longer the in mind, or it's, yeah, not active. And it has been sort of preserved as sort of a nature reserve, kind of, but there's been a lot of question about how to develop it. But it's been closed off for a little while now. And there's like,

tons of different species living inside this quarry. It's really interesting. But Petra is basically has been doing these walks through this quarry, looking at limestone, this mineral that's been mined, and talking about how minerals sort of relate to people, how they pass through.

John (01:17:27.475)

how they become organic and then geological in these different ways and the ways that minerals sort of reconnect back to people and sort of cycle through. And she's been doing like certain workshops, working with the minerals and like, and trying to sort of give, you know,

John (01:17:54.543)

Yeah, minerals and these different aspects of like the landscape, their own agency or their own character, their own dimension. And I think she's been doing really amazing work. There's another couple of artists team that's called Non-Human Nonsense. That's been doing some really great work in Europe. They kind of got...

John (01:18:23.775)

big off of this race a few years ago from this project where they kind of created this pink chicken sculpture that was sort of like, yeah, sort of a way of, it was related to sort of how, sort of a critique of, you know, industrial farming and like how we're gonna, how.

John (01:18:46.499)

archaeologists in the future are going to be able to indicate like when this like ecological shift happened is through like this pink line and the sediments are in the earth and but they've been do a lot of really interesting projects and they've been doing really great work and I would mention cooking sections again they've been they've been doing really fantastic stuff they've been they've done especially with their recent like

Climavor Project, which is about how we change the way we eat in the climate crisis, how do we change our diets, and they really create really beautiful stuff with different species. There's a group in northern Italy that is, I believe they're named...

John (01:19:43.227)

It's sort of a, I think a collective, but they're called Brave New Alps. And they've done a lot of social ecological projects in northern Italy, focusing on the region and the different species that grow there and working with businesses and communities and like the cultural identity of that place to sort of connect, connect those communities.

to the species in the really amazing environment there. And I think they do, I mean, they're really inspiring. And...

John (01:20:29.075)

That's all I got off the top of my head. But there are others out there. I think there's others out there, but I think it's a lot of smaller artists who are doing a lot of interesting stuff. And I can't think of too many really big name design studios or agencies that are sort of getting into these ideas as...

Rebeka (01:20:31.062)

That's great. No, that's a lot.

John (01:20:57.807)

in such a way that is as compelling as some of these smaller projects. And so, yeah. Yeah, but it's something to keep an eye out for in general.

Rebeka (01:21:12.322)

Thanks, John. John, that's fantastic. I can't wait to look into these and to close out. Would you mind giving us one piece of homework? I feel like you actually gave so much throughout this conversation. You know, so many ways to look out for greenwashing and artists to look into and species to connect with, but maybe you could just share your favorite one.

John (01:21:22.531)

Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

John (01:21:35.067)

Yeah, there's a lot of great stuff you could do. I think, yeah, maybe the one, I think I sort of maybe already said it, but one good thing to do is go out, try and find something, try and find a non-human species, find whether it's dead or alive or...

John (01:22:05.315)

plant or fungus or a moss or a fish or a fly, you know, find something and Try to follow it for a little while when you know, of course was like and when I mean Yeah, like follow like whether that means actually physically follow it or or if it's like something you find in the supermarket try and Follow where it came from

and, and, or like try and understand, try and see what you can find about it. I guess, you know, that's one thing. And then, uh, you know, you know, it's been just spent some time thinking about it, looking at it, and if you really want to go the extra mile, then maybe I would say like, try and write or draw something new, like some way that you

feel about it or the way that you think you relate to it in some way or what it means to you. Something that's trying to just express a way that it is a part of your life. And that just may be reiterating like that, oh, I found this in a supermarket. It's in the supermarket. It could be as simple as that. But I think that would be something that's usually a pretty interesting thing to do in my experience.

John (01:23:37.839)

Yeah, thank you so much, Rebeka. It was really great talking to you.

[Music]

That is it for this episode. Thanks for spending this time with us. It would be lovely to hear from you about what you thought of the ideas and perspectives shared. Find links for connecting in the show description, along with ways to find John’s work, and also to see the accompanying blog post.

Thank you to Samuel Cunningham for the podcast editing and to Cosmo Sheldrake for the podcast music, which comes from his song, Pelicans We.

Until next time!

[Music]