Episode 10: Taylor Freesolo Rees on tuning into the heart

For the 10th episode (and the season finale!) of The Heart Gallery Podcast, Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer connects with Taylor Freesolo Rees.

Taylor is a filmmaker, documentarian, storyteller and photographer. She has won numerous film festival awards for her work exploring environmental justice, natural resource issues, the outdoor adventure industry and its various players, nonhuman creatures and our relationships with them, and much much more. Taylor has the ability to deftly weave together myriad threads into complex story tapestries that not only manage to avoid being prescriptive but are undeniably alluring & approachable. As a storytelling mastermind, Taylor excels at showing nuance and presenting compelling questions that invite you into a deeper curiosity. Additionally, and so rarely in spaces of wicked problem-solving, through the way she lives and works Taylor makes a case for play, whimsy, and silliness in the face of serious crises. May this episode with Taylor Freesolo Rees fortify your heart.

See below for Taylor’s three pivotal projects and the podcast transcript.

HW from Taylor: “I love giving homework assignments. I would encourage everybody to go outside, into the city, or into “nature” (it's all nature, it's all urbanization). Just go outside and find the first things that you hear and see. And then, rather than being like, “okay, I hear X and I see Y”, hear again and see again. And then hear again and see again another time. See what happens when you further your attention span into the living world. The living world being earth, which [includes] the biggest cities and the vastest, quietest landscapes. Participating in the sensory experience of being alive is the best practice that teacher Taylor would like to give.”

Some of Taylor's favorite artists: Ayana Young & the For The Wild Podcast, Renan Ozturk, Baloo in the Wild, & cartoons in general:)

Mentioned:

Connect with us: Taylor on her website & @taylorfreesolo; Rebeka on the podcast website & @rebekaryvola.

Thank you Samuel Cunningham for podcast editing.

Thank you Cosmo Sheldrake for use of his song Pelicans We.

Podcast art by Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer.

Heart moves at magic o’clock: Taylor’s 3 pivotal projects

Heart Move #1: The first film project. Greenland, 2005.

Taylor: “Although it doesn't exist anymore*, the first milestone of my creative journey was the film I made in Greenland when I was an undergraduate student. It was the first time I ever made a film, so it was the origin of my process and being like, “oh, okay, I’m not just going to do a career to get a white fence and a husband and do the things”. That was the first time that I was like, “oh, stuff is happening in the world. And I'm in a really lucky position to be able to participate and listen and learn and create and maybe make a film”.

I have a ring from the first summer of the project. I had a wonderful interaction with this older local woman, probably in her 70s or 80s. We sat arm in arm together for a while, and then she gave me this ring. And so she stays with me…How many years later? 17 years later.”

*You can learn about why it no longer exists by listening to the episode:)

Heart Move #2: Directing Ashes to Ashes, a short documentary. 2019.

Taylor: “Ashes to Ashes was such a pivotal project for me because it was the first time that I got to be involved in filmmaking without an agenda or a budget. It was my first self-funded project where I just got to follow [a story] and see where it went.

The filmmaking process was just all about friendship and sharing and vulnerability and trust and love. The story is about a woman, Shirley, on a journey to honor lives lost in the era of lynching. And it’s about Winfred, who was processing the trauma of having been lynched and surviving. Winfred is processing his trauma through art and he’s also questioning whether or not art is this compulsory thing that we do around healing pain.

I think that the answer from the film is, “no, art doesn't fix pain, art doesn't make it go away, art doesn't absolve trauma, but it is human”. Being human is to create new things out of what we go through, which both helps us understand our past as well as helps us to continuously create the future in a way that I find pretty magical.”

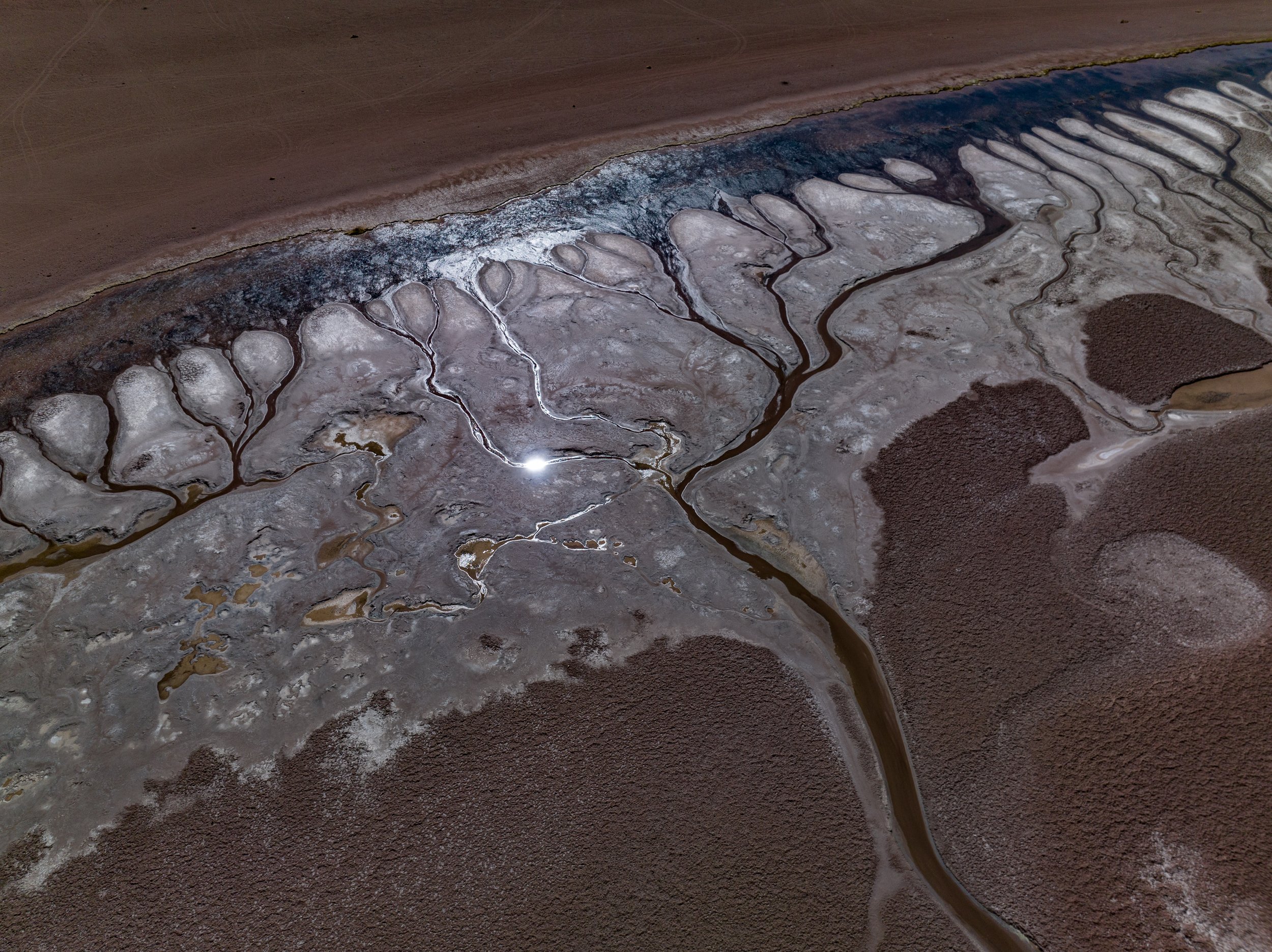

Heart Move #3: Film project about lithium mining in Chile & Argentina. Ongoing.

Taylor: “The third milestone is a film I’m working on around lithium mining. Well, it was about lithium mining, but I'm coming to see that it's really about understanding various pathways to survival that us humans are taking while existing in a complicated network of historic colonialism.

I got into this journey thinking like, “oh my gosh, maybe electric cars are going to save the planet”. I'm really questioning that now, both from a carbon emissions standpoint and also how this is perpetuating sacrifice of some places to save others. The more time I spend in Chile and Argentina on this project, the more I understand that even the people that live in these places are wrestling with the same decisions as we are, which is, “do you take the money from capitalism and try to strengthen yourself and your own personal finances and stability in some way? Or are we going to abandon that for some kind of life that exists outside of the system?” And the answers that I'm getting, and what I'm seeing, is just like, “of course not, we're all in this together”.

I think the most beautiful solutions that we have in front of us are both to question the easy solutions - especially if they make a lot of people a lot of money - while at the same time releasing judgment. We look at what's happening in America and how our country's so divided based on a lot of these ideas and identity politics. And I'm just like, “man, we just really gotta be friends and forgive each other at this point”. The harder we dig down into who's right and who's wrong and who knows enough and who doesn't… it’s just not going to go well.”

Transcript:

Please note: Transcript has been automatically generated.

[music]

Rebeka

Welcome to episode 10 of the heart gallery podcast. This episode is the last one of this first season.

Before I introduce today’s guest, I want to touch on theme that’s come up throughout the season. That is that addressing our ecological and social crises is made more challenging when we get caught in fragmented and piecemeal thinking. Our educational systems tend to still largely focus on siloed systems of understanding our world, and it can feel overwhelming to look at the bigger picture and can feel altogether impossible to look more deeply, closely at complex global challenges. David Orr. As we’ve heard throughout this season, Art can be a valuable tool for expanding our views, creativity, and imagination.

My guest today is a true artistic mastermind at this. She is Taylor Freesolo Rees, filmmaker, documentarian, storyteller and photographer. She has won numerous film festival work for her films exploring, but not limited to, environmental justice, natural resource issues, the outdoor adventure industry and its various players, non human creatures and our relationships with them. More than anyone I’ve ever met, Taylor has the ability to deftly weave together myriad threads into complex story tapestries that are alluring & approachable, . That show nuance, that present compelling questions that invite you into a deeper curiosity. Additionally, so rare in this space of wicked problem solving, Taylor through the way she lives and works, makes a case for play, whimsy, and silliness in the face of serious crises.

I can’t think of a better guest to close season 1 of the heart gallery podcast.

I hope you enjoy.

Rebeka (00:03.476)

Taylor. Hello, Taylor. It's so nice and so funny to be here with you.

Tay (00:06.117)

Hello Rebeka.

Tay (00:14.410)

I know, I'm definitely, I know how annoying it is for podcast listeners to listen to people who knew each other well, to giggle endlessly. And so I'm really putting on my, you know, my A game with just being really grateful, not only to be with you, but to be with all the people who are listening to what you have going on and what I have going on and what we all have going on together, so here is me just putting a little button on that giggle.

Rebeka (00:42.283)

A little bit. I was preparing myself for this.

Tay (00:44.554)

It's a little funny.

Rebeka (00:48.676)

I was preparing myself and I was talking to Pedro and he was like, you can mention you know Taylor, but like don't focus on that. I feel like we're already off on the wrong foot. But maybe because we are chatting casually, I will start by mentioning something from the moment that I met you, or one of the first moments. I don't know if it was the moment, but I remember.

Tay (00:58.364)

Yeah. Yeah. We can, we can.

Rebeka (01:19.016)

grad school we had this orientation activity which was I remember being quite stressed we had to go through the whole entire class I think there was like 150 of us something and we each had to one by one it was so long we each had to stand up we were sitting outside under this big oak tree and we each had to stand up and say something about who we were and what we were interested in and I remember you standing up and saying that you were interested storytelling. And I remember thinking like, what? Who is this whimsical creature? You had this like this energy about you and luckily we got to be together in some of our orientation activities and very quickly I saw that you more than anyone I've ever met in my entire life go through life in like the most playful like experiment oriented, like curious way. And I don't see that lightly because you and I know a lot of whimsical creatures. We're lucky enough to know a lot of very creative people, both in our relationships, in our friend group, and also outside. And I just, I wonder if you wouldn't mind sharing a little bit about how you came to be driven by curiosity, by your connection to nature this very deep exploratory connection to nature that I see, where did this come from for you?

Tay (02:55.319)

Hmm

Tay (02:58.338)

Thanks for that question. I asked myself that just this morning, funny enough, because being in the middle of going through kind of a reorientation or analysis of some way of what I'm doing right now, and whether it's serving me and it's serving my creativity or serving my work, I was like, well, what are my roots? Like, what makes me me? Like, what is unapologetically okay, whether I can affect change or you know, sustain myself financially from it all. And I called my mom, whom I never really like thought necessary. She's an engineer, but we just like started having a chat and we just like very quickly slipped into this conversation around, you know, like what, you know, I was like telling her about this squirrel that I met that like came up to me at this moment. And she was like, well, obviously it was like, you know was mentioning X, Y, and Z. And then we got to chatting about whether or not we would paint our refrigerators or something, I can't exactly remember. And I was like, Oh, like, I think I got it from you. And maybe that's, in some ways, an invitation, like I've never really been one. I mean, I feel like I'm such a like, I'm a free spirit. And every person that gets born, every person, everything that gets born into the earth just comes in with their own

Tay (04:24.350)

self-autonomy and direction and destiny. But in many ways, I really got my sense of playfulness and my curiosity and my sensitivity to the unknown, especially as it's communicated to me through the natural world for my mom, which I just wanna say, I am so excited for you, friend, being just days away from birthing your child. And so like...

Yay! That is so... That is so... It's so... Yeah..

Rebeka (04:55.548)

With that in mind.

Rebeka (04:59.484)

With motherhood, well, sorry to interrupt, with motherhood in mind, can you share some of the practices your mother had with you when you were younger? Like if there were specific things that she did that you did together?

Tay (05:14.182)

Yeah, absolutely. She would never call them practices. I think she's very anti-practice anything. But in hanging out with her, life did always revolve around some very practical things like taking care of yard work, which somehow ended up evolving into picking up pieces of trash that were around the house or around the yard. And then the next thing we knew was mid-afternoon, we'd be making some art project out of said trash.

Tay (05:47.934)

Yeah, and a big part of my childhood with her was always painting pots and planting things in the pots. And in my mind, the story I've at least told myself about that was that there's a really important practice of using your imagination to create a container for something that you want to grow. And maybe that container metaphorically is a pot. And then planting something in it that you needed to take care of. So you know, there's more than just the intention. There's all of the follow through and the nurturing and the watering and the sunshine and the disease and the healing that comes to just taking care of a plant. So if she heard me say this, she would roll her eyes because I know that she didn't look at it in that way, but that's at least like how I interpreted it. And so, yeah, she's wonderful. And yeah.

Rebeka (06:42.676)

She is wonderful and you with your metaphors are also wonderful. Do you, if you look back at your life, do you feel like you've always had this metaphor-driven way of looking at the world? Because that is so tailored. Coming up with some kind of framing for something very, very plain around you. Where did that come from?

Tay (07:04.706)

Good question. Well, I read a book in college that I really loved called The Metaphors We Live By. And I never, I mean, I think the idea of a metaphor is probably too intellectual for a young person to think about, even a person my age that I'm just, what is metaphor. But I will say, like, this book, Metaphors I Live By, played a really important role in my, in my commitment to my partner and my wedding. And in the book, it talks about how we have all these associations through language that help us understand things. So like, Earth is rock, Earth is planet, Earth is this. Like, it's not me, it is me. You know, like our language creates a lot of how we experience things. And one of the metaphors in this book is that, you know, we have a lot of metaphors in our language that point to the fact that love is war, love is conflict, love is illness. I fell in love, you know.

Tay (08:02.462)

No, sorry, argument is war. Love is not often war, but love is definitely this thing that's like, I fell in love, it's out of my control. It came in and come out. And the author proposes this notion that love is collaborative art, which requires the vulnerability of sharing your vision really deeply at the same time that you know that manifesting that vision, if you're going to do it in partnership, requires seeing another person's vision and then how do you make something out of that? You know?

Like how do you really truly collaborate? How do you through love compromise and share a vision and try to see what might be in the middle between two visions or three visions or thousands of visions, millions of visions if we're talking about how we're envisioning the future of the world and how do we include the most amount of people's visions in that, what that looks like on a really practical level and on the practical level of marriage, you know, like living with a partner whom I create with often, that metaphor, that love is collaborative art has certainly guided our path in its ups and downs. So yeah, metaphor is interesting. And...

Tay (09:18.622)

I enjoy that book for sure, if anyone wants to read it.

Rebeka (09:21.916)

Well connected. And I wonder, so thinking about your marriage and thinking about other projects that you're a part of, and marriage is just one of them, you have so many incredible projects that you have been a part of since I've known you.

and obviously a number before as well. And some of the threads that I pick out that are in common across a lot of your projects are environmental and climate justice. You have this deep, seemingly this deep drive to share these secondary and tertiary and further narratives that are often not explored and in other stories on the same issues. And...

Rebeka (10:04.836)

More and more recently, I've been seeing you exploring non-human perspectives. And then, as we have touched on already, there's also a lot of play and wonder and exploration of what is beauty. And I'm wondering if you can speak about what characterizes your different endeavors beyond, I mean, maybe it's love is collaborative art.

Tay (10:45.898)

And I think that that must be true, of course, for anyone on a creative path, or even anyone on a path related to our relationship to the environment, right? Because there's so many ways in which us as human beings, as we participate in civilization and society, multiple human beings that are trying to interpret what is happening, not only just with our relationship to the environment, so much as it's been defined since the 60s, since we started to really realize narratively that, you know, oh, like we got on a path, we've moved in a direction where our actions are causing harm to this thing that we are not just a part of, but depend on. But, you know, how, like as human beings living, we even make sense of life and the universe. And so, yeah, I have been on some different paths, went to grad school.

Prior to that, worked in nonprofit, always found myself driven by story, while in grad school, got to participate in a film festival with you and some other friends, particularly our dear friend, Lexi. And I don't know, and yeah, like what elements of that are play and when do I feel like my playfulness has maybe even come to a point where I'm just like, oh my gosh, is there too much play? Like, is the seriousness of our impending crisis around the environment, like should it require me to be less playful? You know, and then I'm just like, well, at least there's other people out there who are, you know, I don't know, working in these institutions and should I work institutionally? Do I work in this industry or that industry or be more art or be more commerce or, you know, work within media distribution channels or go off into the forest, like I don't, I think that there are just an infinite number of paths that a human being could take in any moment. And for me personally, I've really struggled to do anything other than take the next step in the moment that I'm in. Like I don't have a grand plan. I've never had a grand plan. I can definitely look back and look at the past. That's how it's gotten me here and see a pattern.

Tay (13:02.070)

And sometimes the pattern makes me uncomfortable because it makes me question, well, did I have a goal in mind? Like, am I trying to affect some kind of change? Like, am I an artist? Like, what was, what am I thinking? But...

Tay (13:16.754)

I don't have that answer. So I just, you know, just try to keep going, thankfully with the help of a lot of friends.

Rebeka (13:25.000)

When you look back and you see that pattern or patterns, what is that that you're seeing across with your hindsight?

Tay (13:37.814)

Well, I think prior to being a part of a public education system, my spirit was just very whimsical and I played a lot of dress up. I loved, as many people do around the world and all cultures, just like, yeah, just like I am like a mysterious being with this face paint on and playing dress up with all my friends and building fortresses. But took it so seriously, it basically was conducting a local neighborhood theater in my basement for the kids after school.

Tay (14:07.446)

that brought me a lot of joy. And then, you know, going through high school and college and facing what I know a lot of young people face, which is just like, okay, I'm in this system now. How am I gonna make it, how am I gonna have a job? Am I gonna live a life where I just have a job and do that? And my passion is my life and my family, or am I gonna make my passion my career? And what does that look like? Like once I got to that point, I think that's where the pattern you know, has like a couple layers. And the layer that's always been there is my playful spirit and just my love of life and my, the joy I find collaborating with different people, you know, being a living creature on a living earth is so cool.

Tay (14:53.782)

But it was never like, I'm here to save the world, or I think the world is in crisis, right? But yeah, but like at some point or another in that process, you also learn, I think I learned in my 20s, like what climate change was, like what, really what pollution was, what it meant to live in a world where our actions and our institutions and our industries and our economies were actively destroying ourselves and this like planet that we're a part of. And of course that creates a lot of.

anxiety. And with that comes these waves of pathways, particularly creative pathways, where we're all kind of talking about, okay, well, among the many things that need to happen politically, economically, storytelling plays a role in the shifts of that narrative. And I think I took my passion for being a living human being on earth and definitely tried to fit it into some of those paths, which led me to going to grad school.

being the obvious, like, well, if I get a master's degree in this stuff, like, at least the answers will become so much clearer. And in some ways they did. And certainly, like, the people that we've met, whom are also all on those paths, you know, the connections that we have to each other as we're all trying to figure this out became clearer. But yeah, sorry, I'm just like the most roundabout talker. So to answer your question.

I think the pattern is just like, I feel like fundamentally, I'm a playful human being that really enjoys making art that feels the earth that we're a part of and feels some level of sadness for what we're going through and doesn't really have the answers. And it's trying to fit that into a set of current structures that we have for dealing with that problem, but it's also just very like at any given moment in time, I would love to totally drop what I'm doing and start a new practice with that because yeah, getting too stuck in one path. This just seems like no boy, no, no fun.

Rebeka (16:53.884)

your approaches, Tay, are such a gift. And I think that, like, to go back to that, like, that original meeting time, like when I first encountered you, I recognized that. Like, I think even though I hadn't figured out that I wanted to explore arts, like art in the most general sense of the word,

Rebeka (17:17.772)

I knew that so much wasn't working. Like I had come from this policy background to our grad school program and I was so disenchanted. And then I just, I saw you with your approaches that you were bringing into these like very like formal science, technical policy conversations and classes and spaces. And it just seemed, it just made so much sense. And I think that's just, it's just so fantastic that you've offered that to me and so many other people and that you're doing it in such a visible way in the world now through your own art projects. And I know that before you came to grad school, you were working in research. You were working on a research project for a couple of summers at least, right, in Greenland. And it was during that time, I believe, that you started to bring in, or I guess maybe connect your separated passions of storytelling and also understanding the environment, how did you come to realize that you could be someone? Because I hadn't realized that. You were one of the people that helped me realize, oh, I can do something creative in a traditionally non-creative space. How did you come to have that realization?

Tay (18:35.222)

Things are for me in that way because I loved, I loved, I mean, I can put myself right back in that silly business class that we took and I remember sitting next to you watching you doodle. I was like trying so hard to be like, well, I'm never going to pass this task. Just like hating my life and taking notes and turning to my laughs and you were just doodling away with these little doodles. And I was like, um, and yet like that exploratory, I mean, I say this to like anyone who is trying, who like might find themselves.

Tay (19:04.178)

Or, you know, both ways, either in a non-creative field, maybe trying to bring creativity or something kind of out of the box or new to the space that they're in, or like in a traditionally creative field, trying to find application and structure. Now there's always this like weird phase where you're just kind of awkwardly toying around in an environment or in a group in a way that doesn't make sense and like where I remember you doodling, which has turned into this incredible plethora and ecosystem of art and work that you do. And yeah, when I was in Greenland, I arrived, got to be a part of this incredible group of ecologists, just like a field assistant supporting data collection on how climate change was affecting plants and animals. An

Tay (19:56.818)

Yeah. And showing up and just like seeing too, like, wow, we're entering the space of that has been inhabited by other people and not just those plants and animals. And how interesting is that often science, like hard science is like, well, people, you know, we put the social scientists and the anthropologists on the people. And then a lot of the hard sciences are elsewhere. I mean, that's, that's been changing. That was back in 2004. So a lot of that has changed, I think, but in 2005 when I went to Greenland to see firsthand that dichotomy between the production of knowledge through a scientific lens versus the integration or production of knowledge through conversation and human relationships. I was like, this is crazy. I should make a film. And I remember calling my aunt Marianne that summer, who's just this idol in my life. She's a great aunt.

Tay (20:55.410)

She was in her seventies at the time. She was a Hollywood producer. She actually started the first all female film production company ever in LA. She produced Stanford and Sons and All in the Family. And just this like wonderful woman was in a, you know, in a relationship with a woman when it was totally not okay. And just this hero of mine. And I was like, Aunt Marian, you know, I'm 19 and I am seeing this opportunity to be creative in a very non-creative space. And I kind of want to make a film. And at the time I had never, you know, I've never pressed record on a video camera in my life. So that, like, that was the very first time. And I had taken photos. I always loved taking photos with my friends. And, you know, I was like, what do I do? You know, and I was just, I was imagining her just like handing me the reins, you know, just being like, who you are? And she was like, why don't you go rent a video camera from your library, your local library?

And just being like, oh, I have to figure this out on my own. And what a gift, because that's exactly what I did. I rented a video camera and I still had no real, I mean, she offered other kinds of advice, but really what she did for me that was important for me in that moment is gave me permission and the encouragement to have self-direction. Because I think if, you'd like miss all these really important learning phases when you're starting your creative journey if you don't take them. And so I rented a video camera and the next summer I went to Greenland and interviewed local Inuit community members about what it was like to have scientists come to their landscapes and their homelands and their place and interpret the changes for them. And I had no experience. I looked back and I ended up like editing, I've told this story so many times, I'm sorry if you've heard it, but I ended up editing it to Radiohead music and I threw it on YouTube and it got taken down and I didn't know the laptop at the time and the guy I was dating broke up with me and with that took his laptop and that went, and like there went the, so the film doesn't exist anymore. But yeah, what a special moment to be starting something that you feel in your heart that you wanna bring creativity to.

Tay (23:20.082)

and to like take those first baby steps. So, yeah.

Rebeka (23:25.029)

So kudos on that bravery, that courage. And so sad that the copyright laws took that down because I feel like Thom Yorke would have been a supporter of that early creative exploration of yours, not knowing him.

Tay (23:38.046)

Yeah, Thom, you are a genius. And you wanna somehow contact YouTube and grant permission for that film to resurface. I would love that.

Rebeka (23:47.184)

I'll tell you though, so I've heard pieces of that story. I haven't heard that whole thing. And that was, I'm grateful to have heard that. I'm curious how, if you, maybe this is not something you can pinpoint, but you were there doing, collecting this data and you could have just carried on collecting the data, doing the thing you were supposed to be doing. I think you were an assistant, like some sort of undergraduate assistant at the time. Like, what was it that?

Rebeka (24:13.864)

helped you see that there was an untold story there because you've been telling untold stories since in one way or another. So what was that initial like piece where you realized like, okay, this isn't the full story or I wanna be a part of making this bigger and more expansive. So I'm gonna go ahead and start with this one. So I'm gonna start with this one.

Tay (24:33.438)

Well, I mean, I think like the truth is that the untold story was untold to me, you know, and probably at the time and many years prior and ever since there have been lots of storytellers involved in that place, I would say, both of Indigenous Inuit origin and elsewhere. When I was there, I didn't get a chance to connect with any, you know, journalists who were telling stories. So I was literally coming in through my lens and my angle at the time.

of hard ecology science, right? Academically driven data collection. And that's where I was like, it was for me being like, oh, like I'm seeing something that my mind has never seen before. And that intrigues me. And so I think like that feels important because it's not like the stories are untold or the voices are silent. It's just like I don't know, there's a humility, I think, in understanding. Yeah, it was just me. You know, it was just like, whoa. I went in thinking that I was going to be getting this particular kind of knowledge or understanding, and I was gonna integrate myself in based on that, and I saw this other thing. And so that felt like very untold to me.

But I realized the other day, because I was rewriting my bio, and I was like, oh, my bio is so funny, because it's just like the story is under the surface. And I was like, under the surface for who? Probably my own consciousness, right? And that's kind of great that we're all just individual human beings, and we're all just kind of scratching away at things, and that sometimes you have all the knowledge, and you're super privy, and you're super conscious, and sometimes you're not, you know? And sometimes you're naive, and sometimes when you finally scratch that surface, everyone's like, nice to have you here. We've been doing this for a while, you know? And yeah, I'm not, yeah, brilliant by any means or clever. I just, I was just trying to figure my own way out through it, so.

Rebeka (32:09.621)

As you're talking about, like you're grappling with who you're creating for, I know that one of the dances that you've talked to me about in other conversations is this dance between exploring your passion, you know, like having something that you really want to explore, something you're pulled, some kind of story you're pulled to tell or art that you're pulled to create. And then also there's this...

Rebeka (32:34.732)

other, maybe not completely disconnected, but this more commercially oriented work that's, you know, nicely funded. It's often like high exposure. It does have, you know, an audience. You mentioned this adventure audience that maybe you have on Instagram. And I know that some of your bigger fancier clients are these outdoor industry players. And I'm wondering like how this dance has been for you between the passion art that you're pulled to create in this other art and how you're reconciling that relationship over time.

Tay (33:11.378)

Yeah, I mean, I think like it's interesting to look at my husband Renan because he seems very capable to like push his art forward and wake up every day. And I was very excited to go to these spaces and use these tools. And I mean, I guess if we're speaking specifically about documentary film and in the branded content commercial space, just be like, yeah, this is awesome. There are brands, there are networks that need content and he seamlessly and in a pretty awesome state of flow like can work within that space. And maybe it's, I don't know if it's insecurity or if I just haven't seen some of the stuff in the fringes be funded as well, but I do know like of so many amazing artists, so many amazing artists. And yet you're often like, like the first thing that comes to mind that gets shut down is like, but how do you fund it? And what do the sources of funding wanna pay for these days? And what's commercially viable? And so I do think there's a dance, you know, and I don't, I'm not like, ugh, you know, capitalism doesn't want to fund the best ideas. It's just like, no, capitalism and...

Um, marketing and branding strategies are trying to sell their products. And sometimes that, that those, those like forces can, can bring income and funding towards cool things. And then sometimes there's stuff that just like has to get done outside of that. So, um, I personally really struggle a lot of the time with, I don't know, just like either doubting that my ideas are commercially viable or.

Tay (35:30.730)

I don't know, or maybe just wanting to make shit that doesn't have to have the overhead of like, but did you sell the thing or not?

Rebeka (38:14.288)

I've been lucky to witness many of your film projects over the last few years. And in my mind, I've created this like artificial like two buckets of projects of yours that I've seen. Like there's the one where I see Taylor telling the story that she wants to tell. And it's often justice oriented. You're often going to this secondary or tertiary level of a story. And by that, I mean, like it might be my surface, like you're going below my surface level, but I think you're also going like below like the mainstream surface level. So for example, like I can think of your lithium project that you're working on right now, right? Like, and the way that you're going below

Rebeka (39:13.760)

the surface as I see the surface is like in the mainstream right now, we're having these conversations about electrification, about banning gas powered vehicles, right? And everyone's like very excited and people are buying electric cars and it's this revolution. And here you are making a film about how this is also like, we're just moving from one extractive industry to another. And not only that, but we're not talking about the communities.

that are being affected. So this is like, that's one type of project that I see you doing. And then on the other hand, I see you working for entities like Nat Geo or North Face or others. And I know that you're not always getting to go to that level. Like I know from things you've shared with me that there is this like push and pull where you're saying like, I wanna tell this story and they're saying like, that's nice, but like, let's reel it back in. Let's focus it on this like adventurer.

Let's focus it on this like white adventure, for example. And so I'm wondering if you can speak to like whether those buckets, those two buckets do exist for you and whether maybe you've seen some change happening over your career, because your career is a number of years long at this point. I'm wondering if there's maybe like an increased appetite for this desire that you have to tell those deeper stories, starting to permeate into these more commercial spaces.

Tay (40:43.758)

Yeah, well, I mean, I guess Rebecca, like the answer might be the truth is that like the documentary world definitely has grants and there is a really incredible space where documentary filmmakers get to explore these really deep subjects and a lot of films come out every year that go to those steps and there is funding for them. And so.

Again, just like from my point of view, I have come out of this more commercial world, which has been a huge blessing. I mean, I love a lot of the people that I work with commercially. A lot of my documentary friends are homeless, essentially, you know, would like love to do a commercial. And I have a home with my partner and that's amazing. And a lot of that comes from those relationships and I...

It's, you know, I've, I feel the dichotomy sometimes and like, Oh, if the, if the commercial world could only somehow go deeper, but then a part of me is like, well, I could, you know, I could step outside of commercial work and go apply for those grants too. And so this is maybe the messy, I don't know if this will work for the podcast, but like, yeah, the truth is that I choose to stay with in the commercial world, both because, um,

Tay (41:59.442)

there are longstanding relationships and people I love and I do think you can affect change sometimes from the inside, but yeah, we're like running a business. And also, maybe we can figure out how to reframe this for a question, because I don't know if this is, maybe there's like something within this that can work, but like I've hit a point with that though, that's not working. Like Taylor as an artist has like been like, okay, I'll like work in this space and it'll be fine.

she's miserable. But Taylor has the like, I can go to work, I can have a job and make money and support a family and support, potentially be a support for an extended family. She's fine, she can just go to work and stuff. I don't think everything has to be, every single step of life has to be this tortured artist standpoint. But I, yeah, I do feel like I've come to the point where commercializing at least what I want to be a part of and what I want to make has hit an end. And like I'm in the process of writing sponsors this week and I want to shut down my Instagram because it's just not serving me and I, you know, I don't know, I just like want to get weirder and wilder and return to something like much like more formless and.

Tay (43:23.446)

where just like the commercialization of it is not the point. And I'm just like, yeah, I'll go to work. I'll work at a coffee shop. I'll sling beers at a bar because I am struggling to try to fund my work through marketing industries. It's hard. Some people can do it. I'm struggling personally, but not because the system is broken, just because I just don't think it works for me.

Rebeka (43:49.849)

that's so fair and that's so candid.

Tay (43:52.418)

He's like, you're gonna hear that and you're throwing away money as you speak.

Rebeka (43:59.492)

I wonder if you, like, having seen your husband and having seen maybe others, whether there is like some sort of, like, celebrity level that can be reached, like where you start to have that creative freedom that would make you feel, like, help you access the funds to, you know, bring on board these teams of other people who are living without homes and...

but who have the same passions and desires, creative desires as you. Like, do you think that there is a point where that can be reached, or you think that you have to just really go outside of these commercial systems?

Tay (44:38.670)

Hmm, I mean, that's a really good question. I know a handful of people whom I think have reached a celebrity status, who might feel like are wonderful souls and struggle with the same thing and have, you know, are truly creative human beings and who want to do good for the world, but who, you know, have become such commercial entities as a result. And I've seen people succeed in that who've just been like, yeah, fuck it. I mean, I like

Tay (45:06.050)

figure out how to leverage this platform and take the good with the bad. But it wears on them. Some of my friends who are big time celebrities, I see, I guess I see them crushing. They're doing it regardless of how much it wears on them. And in this moment in time, I'm watching it wear on me and just my tiny, tiny, tiny little version of the hat where I just have a tiny, tiny, tiny fraction of followers or I'm just like, oh, I'm just so uncomfortable with this. And maybe I just need a break, but like, I just also, I don't know, the celebrities of anything is a funny, is a funny world. And, um, there are, I actually wrote a paper on this in grad school and like whether celebrities could affect real change in the climate space, like whether there are, whether they can influence politics and voting tactics and, or personal behaviors, you know, whether they can influence what people buy or not. And.

the jury's out, like they can, ultimately. You know, do, I don't know, do I wanna just like hit the gas and go for as big as I can possibly be? No, I think I'm built for something much, much more closer to the ground. And that's been hard to deal with. And I think it's come from marrying a celebrity of sorts and the inevitable part of deep relationships where you're like, oh, that's what you are. And I'll do that too. And we'll match each other and we'll just like up and up and we'll level up together and we'll do these things. We'll become, we'll try to become more impactful and more powerful and all these, you know, like the, are the society that we live in once is always perpetuating the more. And I find myself just like, so, um, like, yeah, just like really, really deeply exhausted by that. Not that it's wrong, but just that I don't know if I'm built for it.

Rebeka (47:00.369)

Yeah.

Tay (47:00.578)

And it was really hard, really hard thing to accept on some level because I'm like, why not? Maybe I had something to give that I'll like let people down by. And then I'm just like, what? That's, that's so huge. That's like, there's so much hubris in that. Like we're all just human beings. And I think the earth wants of us what it, um, what contains like ease and joy. So.

Rebeka (47:28.668)

I want to take what you said about you feeling like maybe you're built to be closer to the ground and connected to some of your current recent work with creatures and specifically with individuals because this work is so powerful and you shared with me a film that you've been working on connecting with the last two female white rhinos, Najin and Fatu, and you got to connect with them. And then you've also recently had a chance to be working on some awareness raising and potentially some cool projects maybe down the line remains to be seen with Tokitai. I hope I said that right. And this is a killer whale individual who you can talk to us about. And I'm wondering if you can share what those experiences have been like and if maybe those relationships that you've developed with these non-human creatures speak to this desire that you have to be more on the ground with your art efforts.

Tay (48:57.218)

So, so much. Oh my gosh. Yeah. I mean, I got into the story around the two, they're not just even the two last female Northern White Rhinos, they're the two Northern White Rhinos left on earth. There's just two and they're both female and there is a project abound that's working to try to bring them back from the brink of extinction and I'm so grateful to be invited to be a part of that with photographer Amy Vitale and my friends at NetGeo on that one too, and just thinking like, yeah, this is awesome. This is a great story, and it's a part of this big series. But the meaning of it all, like what drives me sleeplessly through nights is my actual interaction with them. And these moments of being able to go and to sit with these two rhinos and literally wonder, like, you know, they have bigger brains than I do. They are communicating subsonally, they're sending vibrations through the ground. And we'll touch upon the orca too, but orcas have more, if you consider the amount of brain matter dedicated to relationships and emotions, per percentage of your body weight and size, orcas are some of the most emotionally intelligent, more capable of storytelling than any creature on earth.

And to be in their presence, you know, it's just like, it barely scratches the surface to say, oh, wow, how cool to be next to a big animal. I have no idea what they're thinking. Like, I just get, it's the only time my mind gets so quiet and my heart gets so quiet and everything just like comes all the way down and my, all these feelings of just like rushing and where's the camera and what's the story and am I gonna get funding and how do I make this thing work? Like all that falls away.

And I find myself in these moments of direct communication and relationship with these beautiful living souls. And I've learned so much. I remember the time that I was in Kenya, probably on my second or third trip for that project, and just like distraught. Like, we exterminated, I mean, we've exterminated many species, but to watch these two rhinos walking themselves into extinction, to grapple with the decades of violence and murder out of just the stupidest of stories. The killing of it all, it just really comes fully into my heart. And I'm just like, ugh, I can't even. The whole time there I am, just like on the ground next to these two rhinos, just looking at them with my eyes watering, just like, I'm so sorry.

Tay (51:55.274)

on behalf of my species that we've brought this to this moment. And then looking back at me, just breathing so calmly, napping in the shade. And it's not like, you know, the interpretation of being like, well, they're just animals. Like they're not hearing you, but they sense, they sense the vibration of what I'm going through. And I can totally sense that their response to that. And of course, like today this would be called anthropomorphizing or whatever, but I just know that they were just, you know, they're okay with the the bigger story that's unfolding. That in the moment before we lose something is not the moment to panic. In the moment before you lose something forever is the moment to like calm yourself and increase your capacity for seeing how you come to the point. When you come to the end of a cycle, whether that's death of, you know, a family member or a loved one or a friend or a whole species or your own life, like...

You know, I just think to be as calm as possible and And allow that to like help you see what's happened to get to this moment is the most powerful thing and so I had to to learn to regulate my own panic and despair around the devastation of how we've impacted planet Earth and how we've And how we've treated our our non-human family for so many years

And that gave me so much strength, like to be in that moment and then to just breathe and to feel their heartbeats in the ground and then to put my heart in the ground and then to just be like, oh yes, like we're in this together and they don't need me to panic and they're not panicking. And it's not that this is not a moment in time where we shouldn't be panicking in some ways, but it's a moment in time to come down to the ground and to listen and to like,

quiet the mind and to quiet the human story and to feel your heart as you feel the heartbeat of the life around you, which are mostly non-human creatures, plants and animals and birds and all these things. And so that lesson is just like, it's just created a ripple effect into my life. And I've gotten to know this orca, Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut is her Lummi name, Tokitai she's called, Lolita is her show name.

Tay (54:21.234)

I refer to her personally as Toki and she's the oldest living orca that's ever been in captivity. She was taken from her home at four years old during the biggest violent cull on orcas in history. It's 1970 in the Salish Sea. They set off dynamite. They, you know, dozens of orcas were killed. Dozens were taken.

And she's the last remaining of that moment. And most captive orcas lived like 20 years. She's been in captivity for over 50 years, I think 54, performing every day for food in a jail cell, like in a jail cell, not even big enough for her entire body to go tip to tail the height of her tank.

Tay (55:13.462)

And a number of years ago, they did some sound recordings. A journalist went in and recorded her at night and they recorded the sound she was making at night. And they compared that to the Orca Sound Network's recordings of the L-Pod. Orcas travel in pods and a lot of these pods, their songs, their calling songs to each other have been recorded. And it turns out that 50 years later, she's still singing the same song as her pod. She's still in this tank 50 years later calling out like, hey if they're still around, like anyone out there. And just the sentience and the intelligence of that animal, it just blew me away. And so, I don't know, I've like done a little bit of filming and I'm trying to help and there's many other film crews involved and playing a small role overall in that project. And she is actually, thank God, like in the process of being released and going home. And I think my creative orientation to that will just be to...

Tay (56:14.630)

to tell what she's taught me in a way in a story. And maybe that might be, I think, an animated short film for kids. But regardless, like, oh my gosh, like talk about seeing the story under the story. And maybe that's just my own naive perception through being this like very Western cultured mind. But I, yeah.

I just think we have so much to learn from animals. And so that's where I want to go. I think with these coming years, I hope.

Rebeka (56:49.588)

I've heard you describe yourself as just a human in some conversations, and I've also heard you describe yourself as an earthling, and I'm wondering if the way you see yourself in relation to the world has shifted as you've developed some of these recent exceptional animal relationships.

Tay (57:18.126)

Mm. I mean, I think those two words hit it spot on. Like, I am just a human. And I think all humans are just earthlings. And we live amongst...

Tay (57:34.494)

a bazillion other earthlings, earthlings being all living creatures on earth. And so yeah, no, I'm...

Tay (57:41.650)

I think that definition feels really true because it just helps me to listen. When I walk into the forest, there's some part of me that's like, once I take pictures of it, it's pretty. But then when you calm down, you start to listen to things and you start to sense things. And then little critters or lizards come out and step on your, come in front of your foot. And if you don't pay attention, you'd easily step on them. And I don't know, it's so fundamental, but it's all pointing towards this thing that many religions, many philosophies, many groups are guiding us towards, which is just like, the more we can increase our capacity to listen to the living world around us, the more we'll learn. And there's no right or wrong. There's no good guy or bad guy right now. And I think we need a tremendous amount of forgiveness and understanding towards each other. Otherwise we'll never get to that place. I mean, imagine if all the animals and the plants held resentment against us. Then the second we woke up to their existence, and started to become a deeper relationship with them, we'd have like, you know, like years of therapy to go through. And I actually think they're just standing around waiting and just being like, wow, thanks for coming around humans. Like we've all been waiting for y'all to like start taking a pension and recognizing that like, you know, we have to do this together as a planet. And some people go to Mars and like, that'll be fine too, but Earth will still be around. And I plan to stay on Earth as long as possible.

Rebeka (59:09.544)

Thinking about these three individuals that you just mentioned, Najin and Fatu and Tokitai, what do you hope, you have this privilege and this opening to connect with them that other people will be able to access through you. And as you're sharing the history of Tokitai, I found myself just having an emotional response and it's so devastating to imagine the amount of suffering that we have caused, not only to this individual but to so many. What do you think is useful, and maybe it's not about being useful, but like what, as the person who gets to be a part of these stories, like what do you want to share about them?

Tay (01:00:06.142)

less about the story itself and more about the process that I got to experience getting there. You know, like basically like a portal or an invitation for anyone to have the same experience with any life form around them. Like I'm not like, guess what everybody, I met an orca, super cool, there's an orca like really fancy. And like here's her story that she shared with me. And as an individual, I'm gonna like make something.

Tay (01:00:35.470)

cool. Like, I just, you know, what my true intention and wish is that we all start to and I think storytelling helps us get there is that we all feel invited to be the own, you know, quote unquote storytellers, which is just the interpreters of our own experience with the living world. And that, you know, that every single person who sees that story about Tokitai, I mean, sure, like between Toki, and Najin, and Fatu, there's some really important things to reconcile with around our treatment of animals over time. Our use of them as resources, the violence that we've caused. I think there's some dark things that we will benefit if we process versus ignore. And on an emotional level, I think that's really important to go to those depths and to feel that sadness. But other than that, like I just, I hope as soon as possible that every human being just gets like delighted by the next time they sit down in the grass and a cricket hops onto their shoe. And rather than just being like, ugh a, cricket, they're like, hello, friend. And just have a moment, because an orca is a rhino, is a cricket, is a human. And the language is happening all the time through sound and vibrations and actions and interactions. And it's just so fun.

Rebeka (01:01:59.928)

And this connects to this other type of work that you've done in the past, like where you're just going to the most crazy places, like skiing across Iceland, or going up some mountain somewhere where no one else would wanna go, very few people. And I've heard you describe that this, like this deep adventure, this adrenaline driven adventure is a way of countering this, I guess, almost sleep inducing complacency of modern life, I'm paraphrasing you here, and it's a way of tackling anxiety that you experience and that I think so many people experience head on. And I'm wondering what your relationship is with that now as you're rethinking about doing more of these kinds of films.

And also for people who maybe don't have access to these kinds of like crazy environments, how can they also access that? Maybe you're getting at that with this, this lovely comment you just made about an orca is a rhino is a grasshopper is a etc etc as a human. But maybe can you speak more to that?

Tay (01:03:18.598)

Yeah, I mean, I think the thing that reminds me of the gifts that I've been given through a life of adventure is my own mortality. And, you know, the second that you face a big health scare in life, or someone that you love faces a big health scare, you're suddenly like, oh my god, every moment counts. Every breath I have, everything I say, everything I hear, every action I take, matters. And that's what going to the craziest places that Earth has helped me to do. I've been so scared. I never really wanted to go, honestly. But when I went there, I definitely got to experience the immediacy of life outside of the deep comfort that modern civilization provides slash takes away, the aliveness that it also you know, my, yeah, so, so sure, adventure, like doing risky things will bring you to that place. But it's funny, because my middle name is actually Freesolo, and I asked my dad the other day how that came about, and I was like, you know, was it because you wanted me to like hang on a cliff edge, you know, without a rope? And he...

Tay (01:04:44.226)

I think through my godfather who gave me the name, Greg Jan, it seemed to be more about the fact that in life there are no safety nets. Like, actually there are no safety nets. Everything that you do, you know, if you close your eyes and pretend it's not happening, you know, you can still go through life. You may or may not be aware of the minute that things change or that life is taken away.

Tay (01:05:08.034)

But the second you realize that there are no safety nets and that every action that you take, every breath that you take, every interaction that you have is really kind of creating your life and is rippling out to everyone. It's kind of exhausting because you're like, oh my God, I have to be awake all the time. I have to pay attention all the time. How could I possibly, how could anyone possibly live in the moment as if they were hanging on a cliff edge? It's way too exhausting, but to like take that down on a nervous system level and just like be with the fact that none of us have any idea how much longer we will live.

Tay (01:05:47.018)

None of us have any idea if we will live another minute.

Tay (01:05:53.342)

And I don't think that the human brain loves that thought. And I'm not always sure that it creates the best cascade of secondary thoughts. Like usually there's a lot of fear, but if you can get over that fear and then just like start to own your own responsibility for your own actions, I think there's something really enlivening about that. And like adventure taught me that, being in extreme environments taught me that. Having health scares has taught me that. Watching people I love go through scary things has taught me that. And I don't live that all the time. I definitely don't walk around like with my eyes wide open as if, you know, I'm like on the edge all the time. But I do try to make it a bit of a life practice to come back to that as often as I can, I think, because it helps me to just appreciate the boundless potential that we have in any moment to, you know, turn left or turn right or listen or, you know, dance or keep going or stop or I don't know, just like be conscious participants.

Tay (01:06:52.062)

one way shape or form.

Rebeka (01:06:55.612)

I just have a couple more questions. I see a couple that would be lovely to ask you just to tie this all up. And I'm wondering, Tae, whether there are, whether you can pinpoint any types of art or stories that you want to see more of in the world, whether you're a part of them or whether they're just something that you're witnessing.

Tay (01:06:56.904)

We love you so much.

Tay (01:07:27.158)

Want? No, I think my desire has nothing to do with it. I think that the earth and all of the 9 billion people on the planet are so full of art and story. And I am just excited to see what happens. Like I don't like need or want. I'm very open. Yeah, I like to be surprised.

Rebeka (01:07:49.548)

And are there, can you think of any art or creative people that you've encountered recently that you have been really encouraged by?

Tay (01:08:04.844)

Um...

Tay (01:08:08.306)

I'm so encouraged by you, Rebeka, because not only have you taken on motherhood, but you've taken on an entirely new form, an iteration of your mind from drawing to try and to interpret like these very complicated meetings amongst people as they wrestle with humans and the environment and justice and all this stuff to like having these conversations. And I can't and like it requires technology. I don't know. I'm not.

Rebeka (01:08:27.090)

Ha ha!

Tay (01:08:38.334)

I don't want to get goopy. So I'm just really, but I'm really inspired by you. I'm really inspired to be here in this moment. I can't describe to you what a gift it is to have this like place to land after a really long series of travel. So I love you so much. Yeah.

Rebeka (01:08:56.780)

Oh, thanks, Day. I think like you, and maybe I've taken this from you, but I'm just making it up as I'm going along. And okay, just a couple more. Can you name three artists or writers, poets, creators that you've encountered throughout your life that have affected your worldview?

Tay (01:09:01.963)

I'm sorry.

Tay (01:09:07.007)

Okay.

Tay (01:09:27.870)

Yeah. Well, another podcast, podcaster, Ayanna Young and her podcast for the wild and the conversations that she's having, which really, really to you as well. Man, thank you, Ayana Young and For the Wild.

Rebeka (01:09:40.700)

Such a nice one.

Tay (01:09:54.614)

I just want to give a big shout out to like cartoons in general, I just feel like cartoons, animated storytelling. And I'm talking about the dawn of digital era, like getting able to watch The Little Mermaid, you know, I mean, we're going to be dealing with screens and AI and computers for the rest of our lives. And to, and just those like, yeah, just like cartoons and animators who continue to, to keep bringing these important themes to the latest like Pixar Disney films, I think are so great. And yeah, the biggest poet in my life is my is well, a bit my husband, but also my dog. And I've brought this up a couple times, but just being able to be with an animal and life in your in the space that's familiar to you and just, you know, to have a dog and…

Anytime I'm like running around and running from the house to the studio and he's just sitting in the yard I'm just like, what are you doing? then I go sit next to him and I just calm down and and I'm just like, oh like oh You're like listening to the poetry of the world

Rebeka (01:11:05.268)

Finally, if you can share one piece of homework with the audience, something to do or look for, a question to ask, what would it be?

Tay (01:11:18.302)

Ah, I love giving homework assignments. I would encourage everybody to, um, to go outside in the city, in, you know, quote unquote nature, it's all nature, it's all urbanization, just like go outside and find what are the first things that you hear and that you see will keep it really simple.

Tay (01:11:46.194)

And then rather than being like, okay, I hear X and I see Y, hear again and see again, and then hear again and see again another time. And just like see what happens when you further your attention span into the living world. And the living world being just earth, which is the biggest cities and the vastest quiet landscapes, just listening and looking and being surprised and like

Yeah, having no concept of why or what it means, just participating in the sensory experience of being alive, I think is the best practice that teacher Taylor would like to give.

Rebeka (01:12:29.204)

Teacher Taylor, Miss Frizzle, at least three layers of the onion, but if you want extra credit, you can peel a couple more. Taylor, that's so beautiful. And I'm so grateful for this beautiful winding river of a conversation. Thank you. Thank you so much for this gift of your time and your perspectives and your heart.

Tay (01:12:35.693)

Yeah.

Tay (01:12:51.766)

Thank you, Rebeka, for hosting the Heart Gallery. We're also excited to be exhibits in this space.

Rebeka (01:13:04.513)

Thank you, Tay.

[music]

Rebeka

Thats it for this episode. Links to Taylor’s work are in the show notes, along with a link to The Heart Gallery blog post where she shares her three pivotal projects.

Thank you to Samuel Cunningham for the podcast editing and to Cosmo Sheldrake for the podcast music, which comes from his song, Pelicans We. The podcast art is created by me. Thank you also to everyone who shared their support and feedback during this first season, with a special shout out to my Pedrito.

It would be wonderful to hear your thoughts about this episode and this season. Otherwise,I’ll be back in a few months with an exceptional group of guests. Hope to see you then and there!

[music]